THERE have been recent calls to reinstate or rejuvenate the idea of “Tanah Melayu” by certain quarters, including former premier Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad.

Since the formation of Malaysia in 1963, the term “Tanah Melayu” has primarily been used in historical or cultural contexts, not as a political or geographical term encompassing all of Malaysia.

Modern Malaysia includes both West (Peninsular) Malaysia and East Malaysia (Sabah and Sarawak).

Evolution of Malaysia

West Malaysia, or Peninsular Malaysia, was historically referred to as “Tanah Melayu” meaning “the land of the Malays”.

This region comprised various Malay sultanates under British protection before 1946. The term “Tanah Melayu” was culturally and ethnically used to signify the Malay homeland.

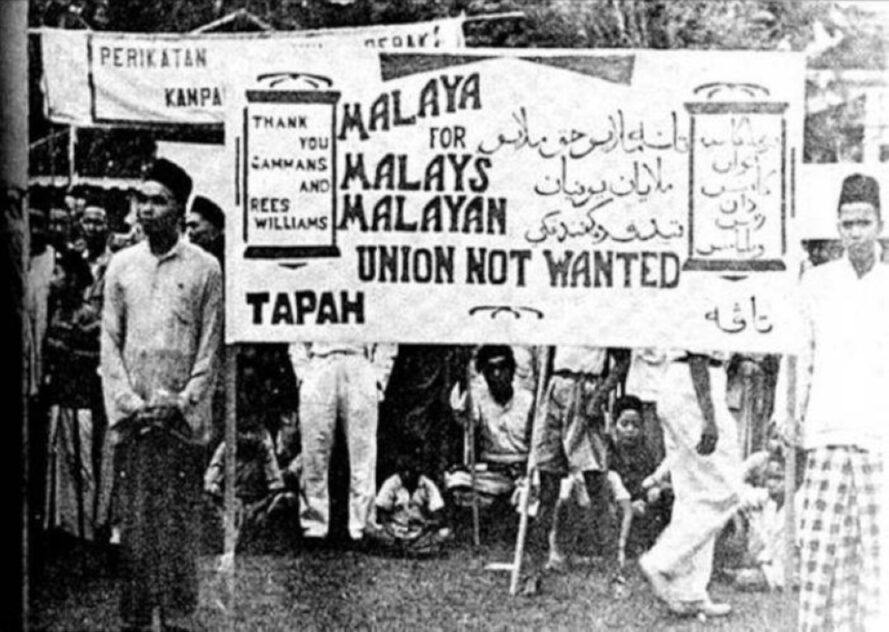

After World War II, the British formed Malayan Union, which was deeply unpopular among Malays as it reduced the powers of the Sultans and granted equal citizenship to non-Malays.

In response, the Federation of Malaya (Persekutuan Tanah Melayu) was established in 1948, restoring the authority of the Malay rulers and reinforcing the political status of the Malays.

In 1957, the Federation of Malaya gained independence, retaining the official name Persekutuan Tanah Melayu.

In 1963, Malaysia was formed through the union of Malaya, Sabah, Sarawak, and initially Singapore. From then onward, Malaysia became the official name.

Today, “Tanah Melayu” is not an official name. It is mainly used in historical, cultural, or nationalist contexts.

Some political groups or individuals may still refer to West Malaysia as Tanah Melayu to emphasise Malay ethnic identity, but it is not recognised in official governance or legal documents.

Legal and political context

The term “Tanah Melayu” holds cultural and emotional significance, particularly in relation to Malay identity and nationalism. However, it has no legal or constitutional standing in modern Malaysia.

The Federal Constitution of Malaysia does not mention “Tanah Melayu”. The legal name of the country is Malaysia. Although the Federation of Malaya (1948–1963) was known in Malay as Persekutuan Tanah Melayu, this changed after the formation of Malaysia in 1963. Legal documents and laws today refer only to “Malaysia,” “the Federation”, or “the States of the Federation.”

Malay nationalist and conservative political groups—such as UMNO and certain factions of PAS—sometimes invoke the term “Tanah Melayu” to assert Malay political dominance.

This is often used to justify policies like Ketuanan Melayu (Malay supremacy) and to frame non-Malay citizenship and rights as conferred rather than inherent.

Such rhetoric influences affirmative action policies, notably Article 153 of the Constitution, which protects the special position of the Malays and Bumiputera communities.

Policies such as the New Economic Policy (NEP) and its successors, which grant preferential treatment in education, business, and employment, are often tied to this narrative.

For many ethnic Malays, Tanah Melayu represents a historical homeland, cultural pride, and Islamic heritage.

However, for non-Malay communities, the term may feel exclusionary, reinforcing the perception that they are perpetual guests or outsiders despite generations of citizenship.

In East Malaysia (Sabah and Sarawak), the term is often met with unease. It may be perceived as Peninsular-centric and potentially marginalising to the unique identities and autonomy of East Malaysians.

Symbolism vs legality

Though not legally binding, the term “Tanah Melayu” remains politically and culturally potent. It is frequently used to assert Malay supremacy, justify affirmative action, and frame national identity either uniting or dividing, depending on the context.

Recent citizenship amendments (2024–2025) have stirred constitutional debates on what it means to be “truly Malaysian”, particularly concerning stateless children and automatic citizenship rights.

During debates on citizenship laws, some lawmakers warned against “eroding the Malay core,” subtly referencing the symbolic weight of Tanah Melayu, even without explicitly naming it.

Can “Tanah Melayu” legally return?

If Sabah and Sarawak were to leave Malaysia, could Tanah Melayu become legally binding once more? Technically, yes—but not automatically.

It would require a major constitutional overhaul.

Malaysia’s current legal structure was created in 1963, when the Federation of Malaya was joined by Sabah, Sarawak, and Singapore. The Constitution defines “Malaysia” as comprising 13 states, not just Peninsular ones.

Should Sabah and Sarawak leave the Federation, the existing political and legal framework would collapse, requiring amendments to the Federal Constitution. Only then—if politically desired—could the name Persekutuan Tanah Melayu be reinstated.

Such a move would carry profound legal and political consequences. Restoring the name “Tanah Melayu” would require parliamentary approval, including a two-thirds majority.

It would likely be perceived domestically and internationally as a regressive or ethno-nationalist shift.

Reverting to “Tanah Melayu” could be interpreted as transforming Malaysia into a Malay-centric state, rather than a multiethnic nation.

This could deepen divisions with non-Malay citizens, including the Orang Asli, and reinforce the notion of Malay-Muslim political supremacy.

Its resurrection would not be automatic and would carry significant political and social repercussions, both within Malaysia and globally. – May 15, 2025

KT Maran is a Focus Malaysia viewer.

The views expressed are solely of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Focus Malaysia.

Main image: The Borneo Post