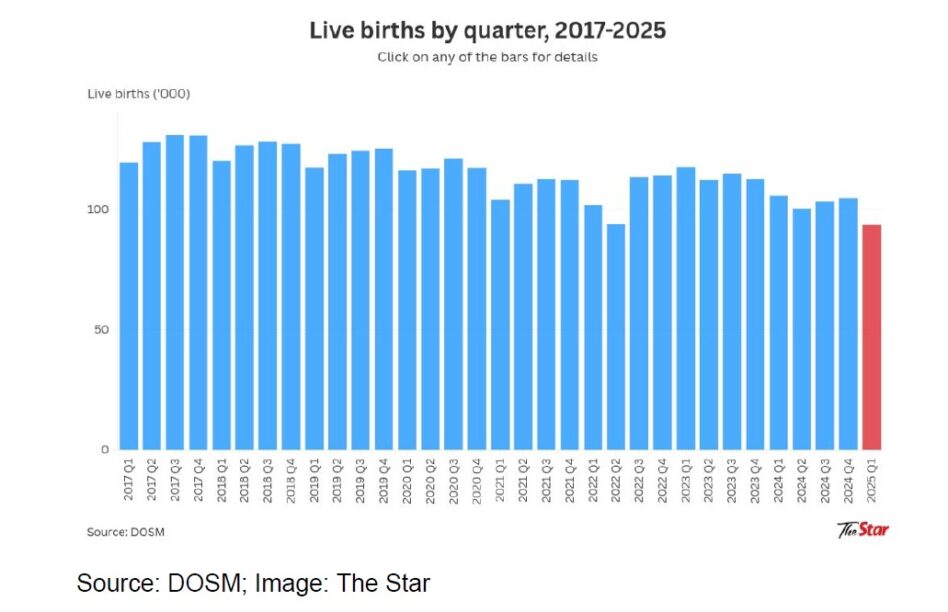

IN its quarterly population report released recently, the Malaysian Department of Statistics (DOSM) reported that the number of live births recorded a decrease of 11.5% to 93,500 births as compared to 105,613 births in the first quarter 2024.

This fertility downturn, combined with rapidly ageing society, poses a profound threat to Malaysia’s economic and social sustainability.

The figure above shows the live births by quarter in Malaysia (2017–2025). Q1 2025 (red bar) shows the lowest number of births on record (93,500). The downward trend highlights an alarming “baby bust” that has been accelerating in recent years.

Declining births, rapid ageing

Fewer young Malaysians are being born, and each subsequent generation shrinks in size. DOSM warns that this phenomenon poses major challenges to demographic structures, economic growth and social balance.

In plain terms, fewer working-age people will be supporting more retirees, which strains our pension funds, healthcare system and economic vitality.

At the same time, Malaysians are living longer and having fewer children. By 2040, over 17% of Malaysians will be seniors (aged 60 and above), which qualify us as an “aged” nation.

By 2057, more than 20% of our citizens are projected to be over 60, which reaches a level where the United Nations (UN) defines it as “super-aged”. This implies fewer taxpayers and caregivers for every elderly person.

In 1970, nearly half our population was under 14, and only 5.5% were over 60; however, today, only about 22% are children while seniors consist of more than doubled to 11.6%.

If this trend continues, who will be there to support and care for our ageing communities, and one day, even us?

The ageing wave is already here. In the face of economic and social crisis, we must think beyond baby bonuses and begin innovating how we support an ageing society.

A ‘social currency’ for future care

Imagine a system where doing good today earns you security tomorrow. By implementing the social currency model, young Malaysians can earn credits by volunteering their time and skills to help others, by assisting the disabled to cross the roads, bringing the elderly to the hospital or just as simply as providing basic tech support for neighbours.

For every hour spent contributing, volunteers would bank “time credits” in a dedicated account. In their older age, they (or even their family members) could redeem those credits for services or care from the communities or partnering organisations.

Essentially, this social currency can turn volunteer hours into a form of savings for future care, which can be interpreted as “paying it forward”.

This isn’t a utopia. Some other countries, such as Japan, which has one of the oldest populations, has initiated a “Fureai Kippu” time-credit system as early as 1970s, in which volunteers earned “love currency” by caring for the elders, which they or their families could soon use for their own care needs.

Other than that, Thailand also set up a government-backed “JitArsa Bank” time bank for volunteers, fully-funded by their Ministry of Older Persons.

Therefore, Malaysia can learn from these models and leapfrog with a programme tailored to our local communities, with the right support.

From community bonds to sustainable ageing

At its heart, this scheme encourages Malaysians to engage within their communities. Young people instead of being isolated by screens every day, they can find purpose in tangible acts of service.

According to a KRI Institute report in 2022, participants in similar time-bank programmes abroad have reported greater life satisfaction and new friends made across age groups. In short, stronger community bonds today mean a more cohesive nation tomorrow.

Other than that, by crowdsourcing eldercare and other social support to willing volunteers, Malaysia can reduce the pressure on our formal welfare and healthcare systems.

Community caregiving can improve access to services and cut costs through local support networks, delaying or even preventing the need for expensive institutional care.

More importantly, social currency bonds the generations together in a fair exchange. In effect, we create a self-sustaining loop of support, in which each generation “pays” into the system with time and “withdraws” support later.

Moreover, by formalising it as a “currency”, the support network becomes reliably exchangeable and not just a matter of charity.

A volunteer can trust that their kindness is recorded and will be reciprocated. Such a system provides a path for creating a world that no one needs to fear being left behind simply because they outlived their relatives or savings.

This is a bold idea but Malaysia has the heart. And now, the need to make it real. It’s time to reimagine how we will care for the people we already know we will have. It benefits both the government and the citizens.

The government doesn’t need to spend more. It needs to invest smarter by mobilising the energy of today’s youth for the needs of tomorrow’s elderly. – May 19, 2025

Yap Wen Min is a policy analyst at HEYA Inc., a non-profit think tank and people’s academy where she focuses on topics such as eldercare, volunteerism and community resilience.

The views expressed are solely of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Focus Malaysia.

Main image: UNFPA