THE avalanche of corruption scandals unearthed in Malaysia involving billions of people’s money-making corruption reflects a way of life that plagues all strata of institutions and society and can pave the pathway to the destruction of the nation and its people.

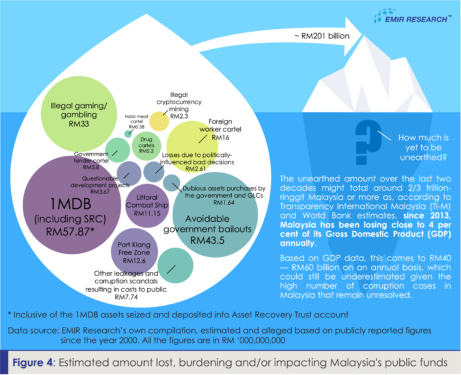

In an ordinary course of business, hearing of billions of ringgit being stolen, whether it is from 1Malaysia Development Bhd (1MDB), SRC International or the littoral combat ship (LCS) project, should have sent shock waves to all in Malaysia.

But did it really send shock waves? Or did the identity politics of race and religion once again subdue the shock waves?

With the worry over corruption being normalised in Malaysia, a natural question arises of whether Malaysia will become a failed state.

In this context, it is an interesting exercise to juxtapose Malaysia’s socio-economic-political life over the last couple of decades with the “template” for poverty and becoming a failed state described in one of the world’s bestselling books — Why Nations Fail by Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) economics professor Daron Acemoglu and Harvard University political scientist James A. Robinson.

The authors, both recognised as leading specialists in contemporary political economy and development economics, suggested a novel explanation behind the vicious cycles of poverty and misery in which some nations (not all) find themselves.

They based this explanation on a synthesis of about 16 years of original research that analysed historical patterns over about 10,000 years, with a geographical spread over all five continents.

Their original theoretical framework is underpinned by multiple complex political economy theories, such as the model of franchise expansion, game theory, the models of kleptocracy and oligarchic society — all hidden behind the simple and intuitive language of the book.

Despite being (perhaps fairly) criticised for missing the multi-faceted nature of economic development and ignoring the supra-national involvement, the scientists still captured a significant predictor of a national failure.

To summarise the entire book in a very concise way: “Institutions decide everything”. Institutions are the formal and informal societal rules of how they function economically, politically, and socially.

Societal changes

Over a long period (centuries and sometimes even millennia), nations accumulate insignificant changes in the level of their social organisation complexity. However, a large-scale change in the external (to the nation) environment occurs at some historical junctions.

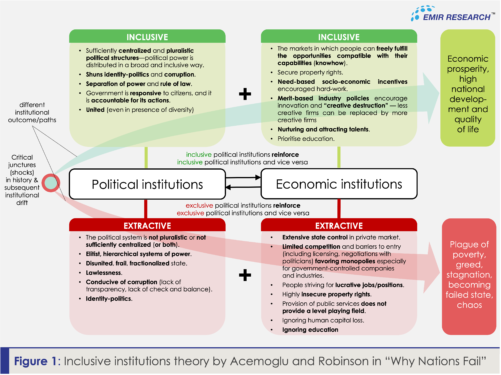

Some societies are able not only to accept these challenges but to adapt and integrate them into their societal organisation via “inclusive institutions” born at this moment. But for other nations, this same historical junction begets the strengthening of pre-existing “extractive institutions” (Figure 1):

The authors are particular in their choice of words. The opposite of “inclusive institutions” they call not just “exclusive” but “extractive” to re-emphasise not only their nature but their very reason. In doing so, they also advance another subtle thesis of the book — the failure of a nation is never by a genuine mistake of the powers to be; the mismanagement is always on purpose!

Extractive economic institutions dynamics — such as extensive state control, entry barriers, regulations limiting competition and favouring monopolies, individuals choosing lucrative occupations and creating a non-level playing field — are there for a reason of creating an unequal society, where solely the “elite and the politically powerful actors” benefit by extracting resources from the nation as a whole.

Extractive economic institutions depend on pre-existing extractive political institutions which are lacking pluralism (recognition and affirmation of diversity within a political body, which is seen to permit the peaceful co-existence of different interests, convictions and lifestyles) or sufficient centralisation (or both) and therefore carry uncontested power to install the extractive economic mechanisms in the first place.

Vice-versa, the extractive political institutions don’t combine well with the inclusive economic institutions made to unlock the process called by the great economist Schumpeter a “creative destruction”.

During this process, old technologies are replaced by new ones, new sectors of the economy attract resources at the expense of old ones, new companies crowd out previously-recognised top performers, new technologies make old equipment and skills unnecessary and upward class transition creates new leaders who can challenge the status quo.

Thus, inclusive institutions and the economic growth they spur produce both winners and losers among economic and political players alike, with the fear of this creative destruction often underlying resistance to creating inclusive economic and political institutions.

Consequently, inclusive and extractive institutions trigger complex feedback loops that can be either positive (virtuous circle) or negative (vicious circle). Inclusive institutions also create sustainable long-term growth of wealth.

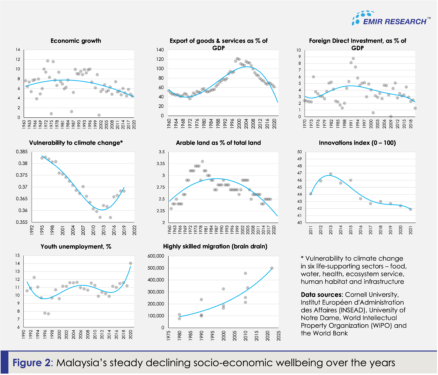

Extractive institutions can also produce economic growth, but it will be unsustainable and short-lived. Recall the statistics presented by EMIR Research in its earlier writings (see Figure 2) and note that structural break happened mainly around the early 2000s.

However, growth under inclusive institutions allows for “creative destruction” and thus supports technological progress and innovation — the sole driver of sustainable economic growth and national prosperity.

Therefore, to be a conceptually powerful and responsible citizen, one must sometimes take the time to read such works as Why Nations Fail. If an average Malaysian is to flip through the pages of this book (or at least have the patience to study Figure 1 in this article carefully), they would certainly recognise the starkly familiar patterns.

What out-of-extractive institutions checklist does Malaysia not have?

Over the last couple of years (mainly COVID-19 pandemic years because crises always helps to write off management flops), our nation has advanced so far in its “institutional drift” towards becoming even more extractive that it prompted Malaysia’s profound scholar and thinker Prof Emeritus Tan Sri Dr. M. Kamal Hassan (who in his entire life of 79 years, never spoke of politics) to write a book, Corruption and Hypocrisy in Malay Muslim Politics.

“In this small and humble work of mine, I am contributing – by the grace of Allah SWT – my thoughts towards the ultimate goal of putting an end to the cancer of political corruption, the pandemic of hypocrisy and the resulting shameful disunity that has plagued the Malay-Muslim community”, said the author.

Highlighting the disunity as an outcome of identity politics (absolutely shameless exploitation of ethnicity and religion), the scholar is addressing the gap insufficiently addressed even by Acemoglu and Robinson in their Why Nations Fail — what political processes lead to the creation and preservation of extractive institutions?

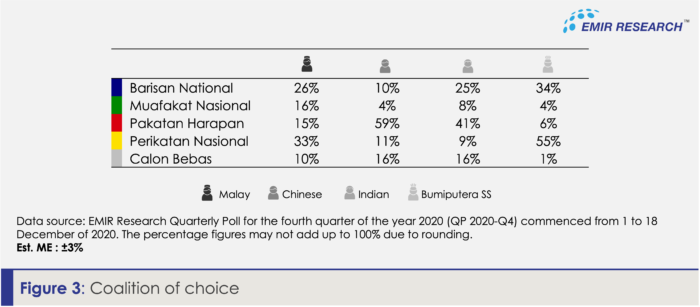

To secure their political survival, extractive Governments have no choice but to play the trump card of identity politics to break and disunite the nation. This is because they probably know the probabilistic tendency: the less dispersed the distribution of citizens’ political preferences, the more the politicians must be concerned about their welfare since the share of supporters is more responsive to the policy choice.

The EMIR Research poll held amidst the pandemic during the fourth quarter of 2020 has shown that the Malay community is the most dispersed regarding their political choice (Figure 3):

By the same token, extractive Governments are not interested in curbing poverty and inequality because citizens’ political preferences would be largely dispersed if inequality among citizens is large.

Not surprising that the devastating and destructive impact of the decades of extractive institutions reign on the nation and specifically on Malay and rural communities (the main grip hold of the ruling political elite) is no longer possible to hide (for statistical evidence, refer to Ruthless colonisation Mat Kilau could not even imagine from July 25, 2022).

But remember, mismanagement of the country is never accidental — it is on purpose! And while citizens close one eye on this, the billions of extracted resources accumulate. The total amount that can be reconstructed from the publicly reported figures (Figure 4) is only the very tip of the iceberg:

However, the authors of Why Nations Fail also observed through various historical case studies that inclusive and extractive institutions can grow from critical junctures (see Figure 1). And the key factor in all the situations where a turn towards inclusive institutions happened was that one or another broad coalition was able to gain enough political force to stand in solidarity against extractive institutions.

Nevertheless, if the extractive political institutions are preserved, the winning group, like its predecessors, remains unrestrained in its use of power. This creates incentives for the winners to maintain extractive political institutions and recreate extractive economic institutions.

Malaysians learned this painful lesson in the aftermath of the 14th General Elections (GE14) when many of the promised inclusive institutional reforms were not implemented at the whims of one or two individuals.

Therefore, in the forthcoming 15th General Elections (GE15), Malaysia’s ability to take a different institutional path is critically dependent on the current opposition’s ability to form a formidable turn-around team composed of individuals not tainted by the support of extractive political institutions.

At the same time, the rakyat needs to remember extractive institutions and how they intentionally keep the nation in an endless loop of misery.

The devastating impact that the COVID-19 pandemic, coupled with the recent global geo-political problems, had on Malaysia’s socio-economic-political life, unlike other nations, should help to keep this memory fresh.

If, during normal times, the deliberate mismanagement of the country can be masked and the rakyat can be deceived by “narrative management” and the creation of pure visibility (mimicking) of management, then the times of crisis highlight all the flaws better than an MRI.

Could the RM210 mil fine and 12-year imprisonment for Datuk Seri Najib Razak and RM970 mil fine and 10-year imprisonment for Datin Seri Rosmah Mansor (the highest fine imposed under the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission or MACC Act 2009 in Malaysia’s history) be construed as the beginning of a greater war against the corruption and extractive institutions in Malaysia? — Sept 13, 2022

Dr Rais Hussin is the CEO of EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.

The views expressed are solely of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Focus Malaysia.

Main photo credit: BBC