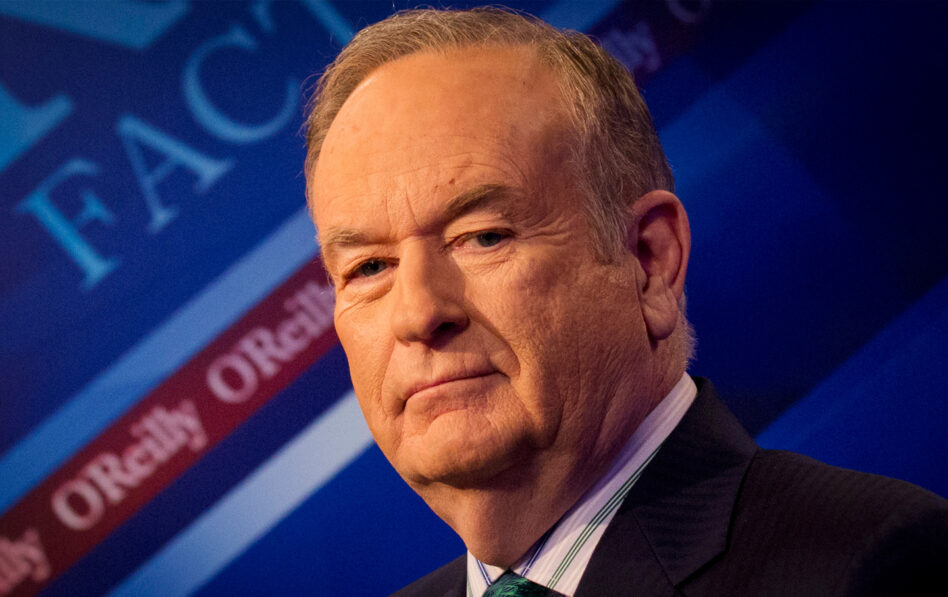

WHEN Bill O’Reilly doubled down on his mockery of Malaysia—scoffing that Malaysians “can’t even buy a little hat” and citing a household income figure of US$5,731 versus US$42,220 in the US—he wasn’t just being flippant.

He was showcasing the danger of lazy statistics. By cherry-picking figures without context, he painted a distorted picture of economic despair and in doing so, revealed a worldview still steeped in colonialist condescension.

A single number doesn’t define prosperity

The $42,220 figure cited by O’Reilly comes from the US Census Bureau’s annual household survey, the Current Population Survey (CPS).

It refers to the median personal income of individuals aged 15 and above in 2023, adjusted for inflation (in what’s called “2023 CPI-U-RS dollars”).

The figure is widely referenced and republished by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (FRED) under the series code MEPAINUSA672N.

For Malaysia, the figure seems to have quoted from CEIC’s “Annual Household Income per Capita” dataset, which draws on official data from the Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM).

The calculation starts with the mean monthly household income in 2022, recorded at RM8,479 (DOSM), which is then annualised, multiplied by the estimated number of households (about 8.662 million in 2022), divided by Malaysia’s mid-year population, and finally converted into US dollars using the average 2022 exchange rate.

Thus, O’Reilly’s framing ignores several key contextual differences:

Different units: He compares income earned by actual individuals in the US to household income per capita in Malaysia, which includes non-earners such as children and elderly dependents. This pulls the Malaysian figure down and inflates the gap.

No purchasing power adjustment: A US dollar buys far more in Malaysia than it does in the US Nominal comparisons ignore this, understating the true standard of living in Malaysia.

Different Timeframe and Inflation Adjustments: The US number is from 2023, inflation-adjusted to constant dollars. The Malaysian number is from 2022, in current prices. So, O’Reilly is comparing different years and price bases, which further muddies the waters.

Even when we use CEIC’s own harmonised household income data series—applied equally to both Malaysia and the US—but adjust for PPP using the World Bank’s official 2022 factor, Malaysia’s household income per capita rises to US$16,857. On that basis, the US–Malaysia income gap is only 2.3 times, not 7 (see Figure 1).

Similarly, GDP per capita (PPP) shows Malaysia at US$34,366 compared to the US at US$78,035—a 2.3 times gap as well. Therefore, O’Reilly’s claim didn’t just miss context—it overstated the disparity by a factor of three.

A Region that Matters

O’Reilly’s deeper implication—that Southeast Asia is irrelevant to the global economy—is just as inaccurate. Malaysia and its ASEAN neighbors are emerging economic powerhouses in their own right.

The image of Southeast Asia as having “no money” also ignores the region’s massive market potential. With over 680 million people, rising middle classes, and growth rates outpacing the West, ASEAN is a prize in global commerce.

This is why trillions in South-South capital (from China, the Middle East, etc) are actively seeking opportunities in these emerging powerhouses.

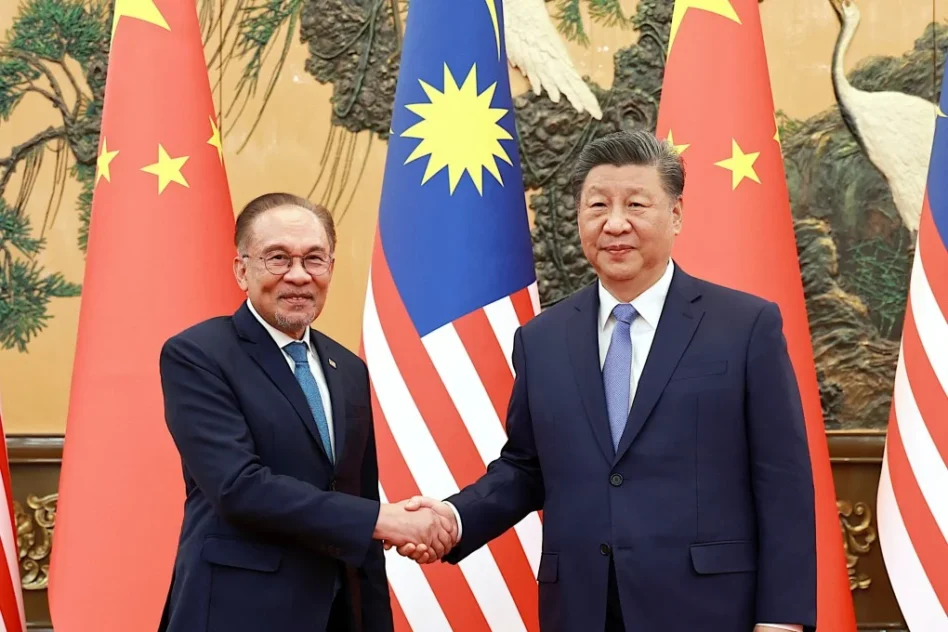

Thus, when Chinese President Xi Jinping visited Malaysia in April 2024, over 30 bilateral cooperation agreements were signed. These weren’t handouts. They were joint ventures—in AI, green tech, and smart infrastructure.

Signs not of desperation, but of ambition to climb the value chain. That strategic openness to both East and West has become far more pronounced under the Madani government.

Similarly, Western tech giants like Google and Microsoft have recently invested significantly in Malaysia’s digital economy.

Malaysia’s economic approach today is pragmatic: be a “bridge, not battleground” between great powers while investing in connectivity, upskilling talent and maintaining macroeconomic stability.

The Colonial lens still lingers

Perhaps most revealing was O’Reilly’s flippant “Ha-ha, I’m a colonialist” remark. That line, paired with his mockery of “small” countries, betrays a mindset that still colours parts of Western commentary.

This view assumes Western dominance as a given and frames non-Western nations as inherently lesser. In the view of the O’Reillies of the world, if a country doesn’t match American standards of wealth, it’s fair game for ridicule.

Prime Minister Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim rightly called such comments “arrogant and ignorant”, shaped by imperial assumptions that no longer hold.

Malaysia is not a dependent economy. It is an upper-middle-income nation with a diversified export base, strong industrial capability, and rising agency.

In 2023, it exported approximately US$74 bil in integrated circuits—23% of total exports—ranking among the world’s top semiconductor exporters.

It also contributes 13% of the global market for backend semiconductor services like testing and packaging. These are not signs of weakness—they reflect systemic relevance and significant potential.

The challenge now is to translate that structural position into broader socioeconomic gains—a goal central to the current administration’s reform agenda.

Unlike the West, which entrenches dominance through IMF conditions, petrodollar hegemony, and the privilege of printing the world’s reserve currency, Malaysia, like many real-economy nations, has had to build its sovereignty from the ground up.

And that hasn’t come easy. Global history shows that leaders who defend sovereignty in both word and deed are often undermined, not just rhetorically, but through sustained economic and political pressure. The nexus between supranational and entrenched local colonialists runs deep.

Malaysia is no exception. The current administration inherited a system long dominated by entrenched interests—what can rightfully be called internal colonialists, sustained in part by external colonialists who, in many ways, never truly left.

Decades of divisive politics and absolute policy inertia have left deep structural challenges. Anwar’s reform agenda marks a break from that legacy, but the path forward remains an uphill climb.

Still, Malaysia continues to push forward. It settles more trade in local currencies, strengthens South-South ties, and plays an active role in shaping regional policy through platforms like ASEAN, RCEP and CPTPP. Its strategy—resilience without retaliation—offers a potential model for others.

So, when O’Reilly mocks Malaysia’s outreach to China, he misses the point. Kuala Lumpur isn’t choosing sides, it’s choosing independence. It welcomes both East and West on terms that serve mutual national interest.

Next time someone chuckles about who “has money,” remember: context matters. Malaysia’s story—of grit, growth, and strategic savvy—is far more compelling than a drive-by income comparison.

Dismissing a country based on a single, unadjusted figure isn’t just bad analysis; it’s a relic of a fading worldview.

In a world of shifting power, it’s not the loudest voices that lead, but those with the clearest compass. – May 2, 2025

Dr Rais Hussin is the Founder of EMIR Research, a think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.

The views expressed are solely of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Focus Malaysia.

Main image: Reuters