MOST recently, two men in their 50s – one foreigner and one local – died on their hiking trips in Malaysia.

French tourist Marc Anthoine Anne Mane, 52, collapsed while hiking Gunung Jasar in Cameron Highlands while a Sarawakian, 51, was on his way up to the Panar Laban base camp on Mount Kinabalu when he collapsed.

Rescue teams who attended to both men failed to revive them with cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

Earlier in February this year, the AP news agency reported of a 67-year-old ice climber from Florida who had collapsed while hiking up Mount Willard in New Hampshire.

The three fatal incidents reignite concerns that older athletes who deem themselves fit should perhaps take a step back when embarking on tedious/strenuous forms of exercise in the likes of mountain climbing/biking, full marathon (42km), endurance swimming or heavy workouts.

This is primarily so as chronic extreme exercises can lead to heart damage/rhythm disorders and especially so for those with genetic risk factors (whether aware or unaware).

While hiking/mountain biking is a great full-body workout that brings many health benefits with fairly low risk of injuries, it would perhaps be wiser to consult a medical practitioner who can run a quick stress test on one’s overall physical fitness prior to embarking on any strenuous activity.

Like the virtue of eating in moderation as a better way of dieting, perhaps it is wise for older athletes not to over-exert themselves by going the full distance or simply choose less difficult trails in the case of mountain biking (i.e by cycling on flat terrains but for a longer distance).

For those older marathon freaks, they need not hang their running shoes but consider ‘backpedalling their tempo a little’ by pursuing jogging or even brisk walking instead of pushing the limits of their physical capabilities to the extreme.

A study done on marathon runners found that even after finishing extreme running events, athletes’ blood samples contain biomarkers associated with heart damage.

These damage indicators usually go away by themselves – but when the heart endures extreme physical stress over and over – the temporary damage may lead to re-modelling of the heart or physical changes such as thicker heart walls and scarring of the heart.

Moreover, research found evidence that high intensity exercise can acutely increase the risk for sudden cardiac arrest or sudden cardiac death in individuals with an underlying cardiac disease.

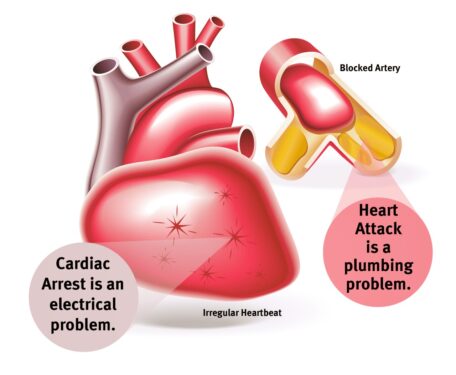

For the uninitiated, there is a need to draw the distinction between a heart attack and cardiac arrest here.

A heart attack stems from a circulation or “plumbing” problem of the heart, according to the Sudden Cardiac Arrest Association. It happens when a sudden blockage in a coronary artery severely reduces or cuts off blood flow to the heart, thus damaging heart muscle.

In contrast, a sudden cardiac arrest is due to an “electrical” problem in the heart. It happens when electrical signals that control the heart’s pumping ability essentially short-circuit. As such, the heart may all of a sudden, beat dangerously fast, causing its ventricles – its main pumping chambers – to quiver or flutter instead of pumping blood in a coordinated fashion.

This rhythm disturbance – known as “ventricular fibrillation” to cardiologists – can occur in response to an underlying heart condition that may or may not have been detected. – Aug 14, 2022

Photo credit: Luminis Health