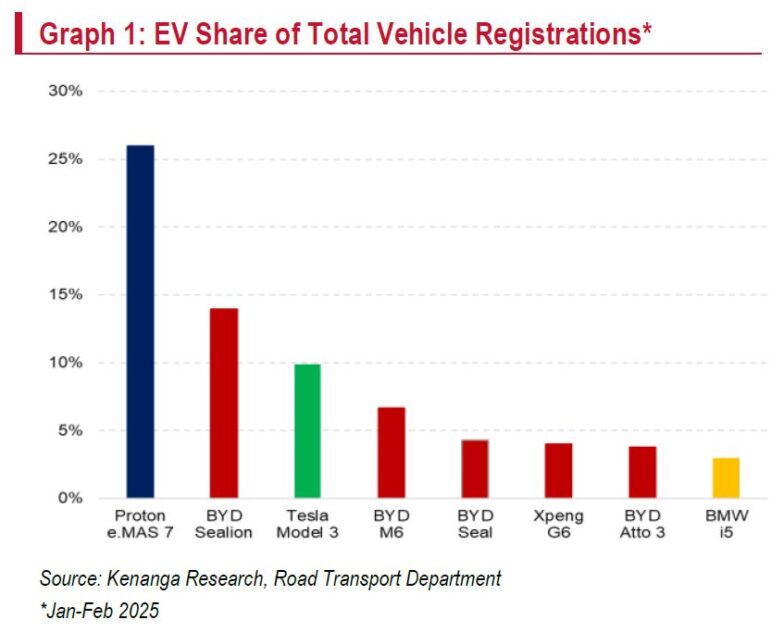

THE market for electric vehicles (EV) is growing, but internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs) still dominate with a share of more than 97%.

Proton e.MAS—Malaysia’s first national brand EV, is expected to spur demand, but EV penetration lags behind Thailand and Vietnam.

The new Proton e.MAS competes directly BYD Dolphin, cost-wise, and BYD Atto 3, segment-wise, two Chinese EVs with established battery efficiency and range.

A quick survey of our EV Day participants reveals strong optimism on EVs, yet admits adoption remains too slow due to concerns over charging infrastructure.

The key challenges include:

1/ most urban Malaysians live in high-rise apartments with limited access to charging facilities.

2/ Retrofitting older buildings for EV charging is costly and developers lack incentives.

3/ Public charging stations are sparse, fuelling range anxiety, particularly for intercity travel.

While the government targets 10.0k charging points by 2025, the rollout has been slow, with private operators seeking clearer revenue models before scaling investments. Current EV-to-charger ratio currently stands at 1:11.

To hit a ratio of 1:8 and support 740.0k EVs (20.0% market share target) by 2030, 92.0k chargers are needed nationwide, requiring significant policy support and private-sector participation.

EVs still seen as luxury vehicles remain a key adoption hurdle. Although prices are declining, upfront costs remain out of reach for the B40 and lower M40 income groups.

The issue extends beyond just sticker prices. While EVs offer lower long-term costs due to fuel and maintenance savings, many consumers focus on initial purchase prices rather than long-term financial benefits.

Malaysia’s EV incentives primarily focus on import duty exemptions rather than direct consumer rebates.

In contrast, Thailand and Indonesia offer purchase subsidies to encourage adoption, making EVs more accessible to middle-income buyers.

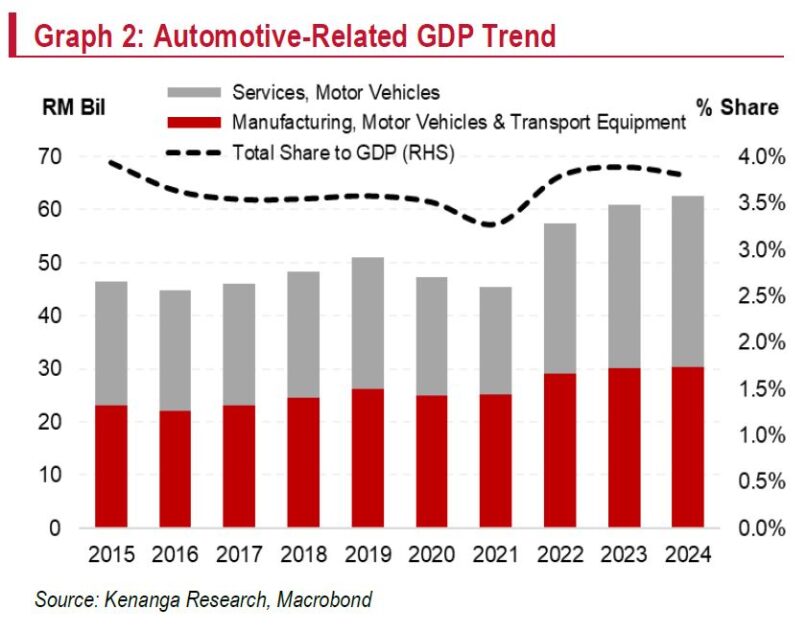

The EV transition is not expected to significantly increase the automotive sector’s contribution to gross domestic product (GDP) in the short term.

Instead, it will catalyse a structural shift from traditional ICE-based production to high-tech, software-driven EV manufacturing.

The ICE vehicle industry, including manufacturing, assembly, the related supply chain, and associated services, accounted for approximately 3.8% of Malaysia’s GDP in 2024 (2023: 3.9%), supporting thousands of jobs and income for the people.

This sector has been largely driven by key players such as Proton, Perodua, and international automakers with local production facilities for many decades.

The adoption of EVs will reshape Malaysia’s automotive sector rather than significantly expand its GDP contribution.

This is partly because the transition from ICE to EV production will require supply chain reconfiguration, reducing demand for existing conventional engine components but will be gradually offset with increasing investments in EV-related technologies such as batteries, semiconductors, and software-driven mobility services.

EV production requires fewer components, particularly mechanical parts, but requires more investment in battery tech, semiconductors, and electronics.

Over time, value will shift from physical hardware to embedded software and services.

Achieving the National Automotive Policy (NAP2020) goal of 10.0% GDP contribution, or RM104.2 bil value with a total production volume of 1.47 mil units by 2030 (20.0% for Evs and Hyrbrids) for the automotive sector remains ambitious given Malaysia’s small domestic market size, which limits production scale.

Then there is the intense regional competition from Thailand and Indonesia with more mature EV ecosystems.

Also is challenging with the limited vertical integration, especially in battery manufacturing.—Mar 28, 2025

Main image: evpedia