DESPITE the broad publicity, all sort of advocacy and lobbying by various interested parties involved, the so-called single wholesale network (SWN) model proposition by Digital National Bhd (DNB), as it stands today, does not hold water from the perspectives of nation building, technical feasibility, financial and commercial viability as well as governance and integrity.

Therefore, this matter deserves urgent and closest attention, the highest level of scrutiny, radical transparency, and an open and extensive public debate. Writing wide-page advertorial content that, in fact, raises even more critical questions and self-contradictions than providing definitive answers is one thing.

However, it takes a whole new level of viability, economic sense and feasibility to withstand open and live public debate with experts from across the industries.

In this series of articles, EMIR Research invites the public and policymakers to critically relook into all the publicly available information surrounding DNB-led SWN proposal that transpires so far from those same critical angles—technical feasibility; financial and commercial viability; governance and integrity and of course widely-claimed intergenerational impact on the national wellbeing.

This part will focus on technical feasibility and financial viability, while the next part will cover governance and integrity and impact on the nation.

Technical constraints and considerations under the DNB-proposed model

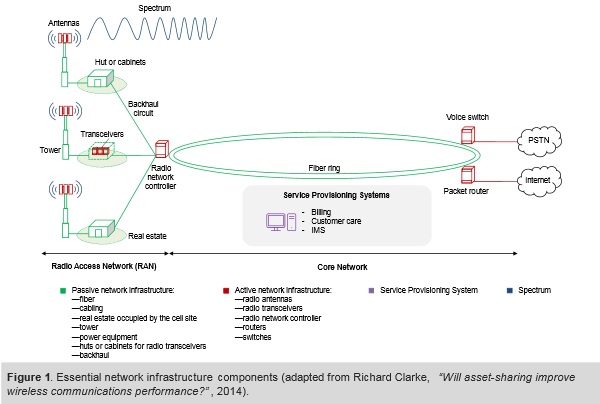

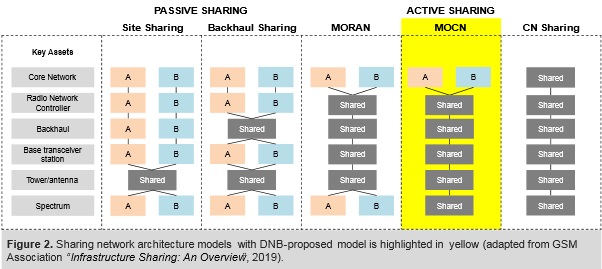

The following figures presenting essential network architecture components and sharing architecture models are instrumental for this discussion.

Although conceptually appealing, network asset-sharing is not always economically efficient, productive or beneficial to the end customers. It rather a complicates the matter which requires systems thinking analysis.

Based on publicly available information, DNB proposes Multi-Operator Core Networks (MOCN) model (Figure 2)—sharing active and passive Radio Access Network (RAN) as well as spectrum.

Technically, it is quite easy to share the passive infrastructure of RAN as it is very generic among the Mobile Network Operators (MNOs) and different mobile wireless technologies (see Figure 1). Also, economically, it is the most appealing as passive RAN constitutes the highest cost to MNOs.

Therefore, it offers the greatest opportunity for deriving benefits without serious efficiency diminution in other aspects of network operation.

As for sharing of active RAN, it is possible only if the radio technology employed by the MNOs is similar—that is what DNB proposes to be built by Ericsson.

In contrast, spectrum sharing can be the most challenging, especially between like users, as it is in the case of MNOs.

Between like uses, spectrum sharing is possible by either geographic or temporal or frequency separation. However, the geographic and temporal separation is not possible in the case of the existing Malaysia MNOs landscape.

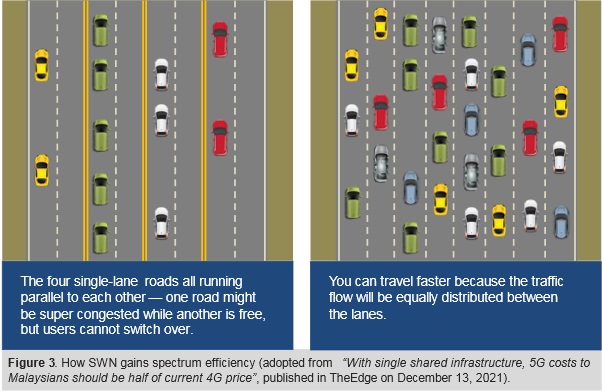

Furthermore, now DNB proposes to get away with the frequency separation (by frequency band) to achieve claimed greater “spectrum efficiency”.

The DNB proponents explain this “spectrum efficiency” with a rather simplistic highway example (Figure 3).

However, in reality, spectrum sharing among like uses in the same geographic area and with similar time usage patterns is possible but can become quickly economically inefficient due to extra RAN costs.

Therefore, this must be tested and confirmed to convince MNOs that the resulting quality for their operation (and for the end consumers) is not interrupted while significant cost savings are produced.

As such, delivering “spectrum efficiency” can implicate the number of antennas, the distance between antennas on a tower, which would impact tower size, or even the necessity to deploy separate transceivers and, therefore, significantly escalate the cost of RANs and, in effect, become the exact duplication, which DNB claims to overcome.

Furthermore, unlike passive RAN sharing, active RAN and spectrum sharing can have an undesirable impact on competition among the MNOs, which DNB is trying to avoid in the first place.

It is unlikely that MNOs would agree to share active RAN if there is no way to accommodate multiple frequency bands. This is because the active RAN equipment and spectrum bands are the critical assets for maintaining the long-term competitive advantage by MNOs in terms of quality or price, or both.

While DNB-proposed MOCN model makes competition possible only on service-provisioning characteristics such as price plans, usage quota, customer service etc.—attributes that competitors can copy quickly and easily.

Note that at the same time, under the MOCN model, MNOs can no longer guarantee the quality of network connection itself and related customer service because they now have to rely on DNB for technical maintenance of the active RAN infrastructure.

With the above, we come to the crux of the whole venture—bridging the digital divide. If sharing and expansion of only passive RAN infrastructure, which is exceptionally scarce in our rural areas and has no added-value for MNOs, will undoubtedly motivate MNOs to come faster to the rural areas with their offerings, be it 4G or 5G, DNB-proposed MOCN model will have the precise opposite effect as being competitively malign.

In other words, if Malaysia needs a monopoly to solve its internet access problem on a nationwide scale, then it should be a neutral entity controlled by the Government and tasked to build, operate and maintain passive RAN infrastructure with open access to all licensees.

This entity can initially focus on new areas but, if need be, acquire the existing infrastructure on a willing buyer/willing seller basis. This was the proposition by Dr Mohamed Awang Lah, whom we can rightfully call “Father of Malaysian Internet”.

It is worth emphasising that this arrangement, where the Government addresses inefficiencies in passive (non-value-adding) infrastructure (which are generally generic across MNOs) will naturally address the problem of national rollout contingency by mitigating single-point failures and delays. – Jan 15, 2022

Rais Hussin, Margarita Peredaryenko and Ameen Kamal are part of the research team of EMIR Research.

The views expressed are solely of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Focus Malaysia.