IN the second part of this article, we will analyse the financial and commercial viability of Digital Nasional Bhd’s (DNB) 5G rollout and how certain issues need to be addressed.

Financial and commercial viability

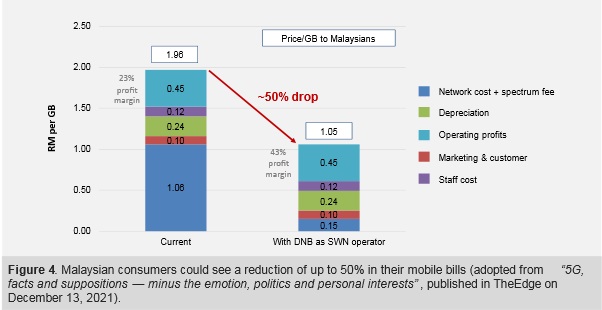

The multi-operator core network (MOCN) model proponents claim that it will enable mobile network operators (MNOs) to provide lower prices (see Figure 4). However, the justification appears to be somewhat misplaced. It would make more sense to discuss the issue in terms of operating leverage and breakeven analysis—important costs dynamics.

Under the current (non-MOCN) model, the MNOs business model has high operating leverage. In other words, the cost structure is such that high upfront fixed cost comes from laying down the network infrastructure—passive and active—and spectrum licensing.

Nevertheless, these fixed costs can be quickly overcome (achieve breakeven) given the large subscription base and traffic volume. After the breakeven, due to low variable costs, nearly every ringgit goes into operating profit.

Note that the sales volume is almost certain and even constantly growing due to the recent transition to the low-touch economy and 4IR, making this leveraged model quite a lucrative business.

However, under the proposed MOCN model for the 5G rollout, the MNOs would not have fixed costs in the form of investment in passive and active infrastructure. Instead, they would now have a new element (spectrum fee) to their variable costs, which would quickly eat into their operating profit margin given high sales volume. So now we can see how Figure 1 from the previous article can be misleading.

Something that quickly eats into operating profit margin and deprives you of operating leverage would certainly not encourage the MNOs to provide lower prices.

In contrast, if DNB could reduce MNOs’ major fixed costs through owning only passive RAN infrastructure without cutting into MNOs’ variable costs, MNOs could overcome their fixed costs faster and have more room for a price reduction.

Nevertheless, under the DNB-proposed MOCN model, DNB officials claim a new variable cost element, which now rightfully could be called spectrum “fee”, would be very low – at least less than 20 sen per GB. However, it is unclear how DNB can ascertain this low cost, given its own cost structure.

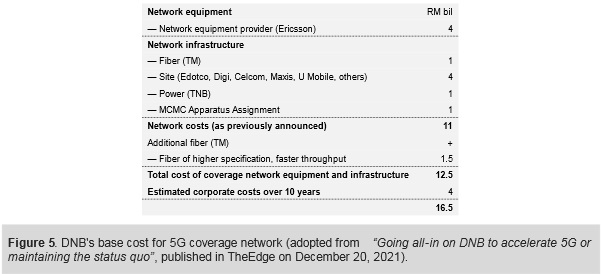

The DNB indicated that, since they do not own the passive RAN infrastructure themselves, it will lease it from the MNOs: “fiber” (most likely bandwidth through fiber) from Telekom Malaysia, site from Edotco, Digi, Celcom, Maxis, U Mobile and others—projected to amount to RM6.5 bil in total over 10 years (Figure 5). Furthermore, Ericsson will build active RAN (another RM4 bil over ten years).

On top of that, another RM4 bil as estimated corporate costs over 10 years for an entity that nearly owns nothing, does nothing, except playing a role of a middleman of a kind, simply suggest itself for more scrutiny and breakdown.

Another interesting question suggests itself—would not MNOs be incentivised to set the lease cost for their passive infrastructure to offset as much as possible the spectrum fee?

They probably would if they could since not all of them own a lot of passive infrastructure except the Government-owned Telekom Malaysia (near monopoly), namely DiGi and Maxis, which brings another interesting perspective on the DNB proposed model.

Rolling out 5G towers in rural areas

Furthermore, the above-estimated costs (Figure 5) might be well underestimated given the specifics of 5G technology—possible hidden costs that were either not laid out transparently or not considered thoughtfully.

For example, as indicated above, the proposed 10,000 towers would be certainly not enough to provide projected coverage targets by DNB (90% coverage in populated areas by 2027).

As reported by MalaysianWireless, Malaysia had nearly 23,000 4G LTE towers in 2018, covering roughly 80% of the population. So, essentially, how would having less than half the number of sites as 4G towers provide even broader coverage when 5G travels more than 50 times less the distance of 4G?

Practically, 4G wavelengths have a range of about two miles while 5G wavelengths only have a range of about 500 meters (about 6 times less than 4G). This means instead of one tower 5G requires 36 towers to cover the same radius as 4G.

Science Insider managing producer Michelle Yan provided examples where such towers or antennae could include every lamppost, traffic light etc. to ensure signal consistency since foliage, trees, and other physical barriers such as building structures (walls etc.) can block 5G signals (think of rural area again).

It is also unclear how having multiple local repeaters to access 5G signals (such as in people’s homes or in office buildings) will impact the cost to end-consumers.

Also, DNB’s proposition is to avoid cost duplication by MNOs in providing the passive and active infrastructure. However, they are not transparent about how such duplication factors into their costs to offer reliability, resilience, and redundancy—essential network architecture requirements.

Furthermore, DNB does not disclose how much cost can escalate due to the necessity of significant RAN infrastructure expansion to even make the “efficient spectrum” sharing possible.

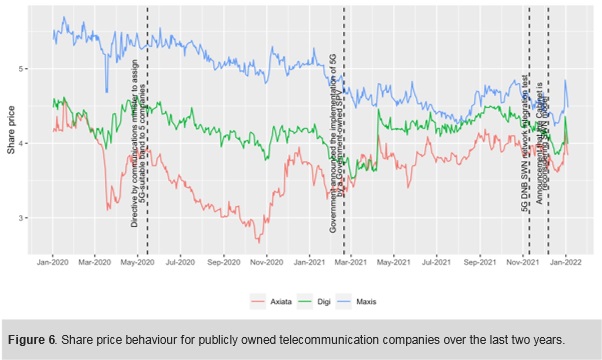

Coming back to operating leverage, removal of it from MNOs’ cost structure will moderate their share prices and have negative implications for dividends (currently received by government investment arms and general public perhaps for their retirement portfolios) or further innovation or both.

Note how prices have ranged over the entire period of DNB-led SWN decision uncertainty (Figure 6).

Needless to mention the spillover effect that this whole deal will have on the foreign equity and direct investment in Malaysia, which we have been losing drastically over the last four years. For example, by the end-2021, Bursa Malaysia’s foreign shareholding already fell to 14.5%, the lowest on record, as reported by TheEdgeMarkets.com.

From an investor’s point of view, it is difficult to imagine one willing to contribute towards capital-intensive resources, especially critical to the infrastructure, in a country with highly inconsistent and irrational policies.

As we can see, the DNB proposition debate is a complex issue with numerous far-reaching implications for our economy and national future. Such fateful decision making cannot happen behind closed doors.

It requires full transparency of all relevant data (pertaining to ALL relevant costs and benefits) to verify and substantiate technical, economic and financial assumptions and necessitates systems thinking approaches brought to light in a live public debate.

The outcome must be a synergistic win-win arrangement with respect to the cost-benefit for all stakeholders. – Jan 16, 2021

Rais Hussin, Margarita Peredaryenko and Ameen Kamal are part of the research team of EMIR Research.

The views expressed are solely of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Focus Malaysia.