AS a case study on past policy target inconsistencies, we can look into rice’s self-sufficiency level (SSL) targets over the past many decades.

From up to 100% SSL in the 1970s and 1980s, it dropped to 80%-85% in between the 1980s to 1990s and stagnated at a low 65% between 2000 to 2010.

The National Agricultural Policy (NAP 1.0) ran between 2010 to 2020 had a 70% rice SSL target, but 2019 data reported by the Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM) showed only 63% rice SSL. Even this low figure could be overestimated given potential issues of rice smuggled into the country.

Needless to say, the low SSL figure is a highly worrying food insecurity situation as rice is a staple food.

Cash crop vs food crop

The above concerning dynamics are not surprising when confronted with numbers revealing how starting from 1960 to the present the industrial commodities and cash crops with their economic appeal gradually but massively overtook land mass in Malaysia limiting the production of food crops.

According to Shevade and Loboda, 2019, “oil palm plantations accounted for the largest area under industrial tree crops in Malaysia by 1990 and by 2010 oil palm plantations covered 20% of Peninsula Malaysia”.

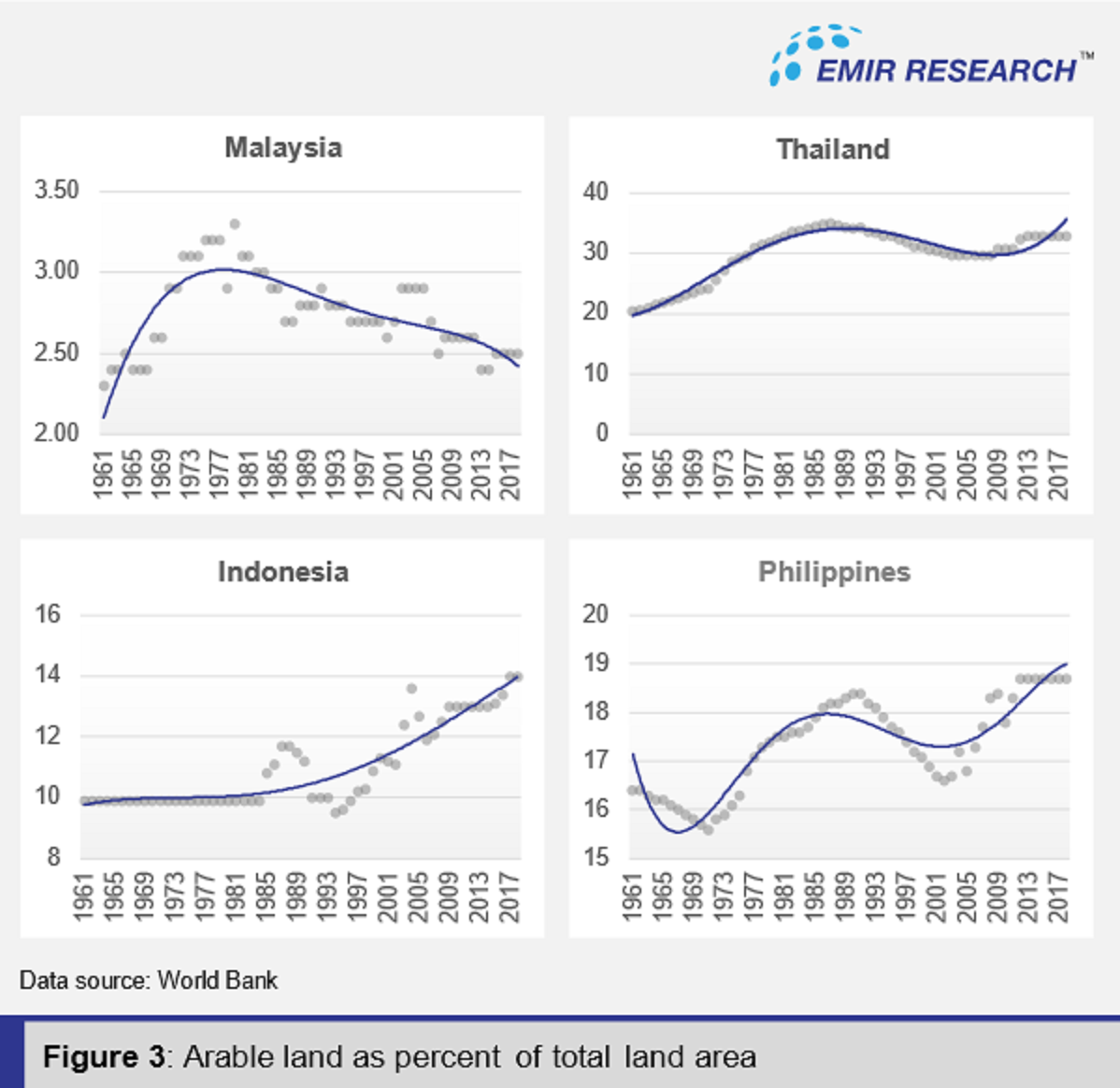

However, the arable land, defined by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) as land currently used, or potentially capable of being used, to grow seasonal food crops, as the percentage of total land area, while already being many times lower than our regional peers in 1980s (see Figure 3 and note the difference in graphs scale), has further shrunk to meagre 2.5% in 2018.

Economically-driven policy shifts resulted in Malaysia overlooking food security as a matter of national security.

Therefore, when trade routes were halted at the start of COVID-19, Malaysia had to resort to knocking on the doors of other nations to push for rice imports.

Reports indicate that the production of rice in Malaysia is not as cost-efficient as in neighbouring countries such as Thailand.

Researchers from Universiti Utara Malaysia noted that this could be due to lower international market pricing for rice being below Malaysia’s average production cost. This explains why rice and paddy is a heavily subsidised industry.

Despite this, and especially for higher-end/exotic rice varieties, it could be cheaper to import. In short, our paddy industry is not competitive.

Thus, approaching self-sufficiency from the national security perspective must transcend purely economic reasons—we would not be able to eat cash, or drink oil palm during times of crisis.

Furthermore, investing heavily in national technology-infused agriculture or AgriTech is an excellent market proposition for Malaysia with a captive market of more than 32 million people and never-ending demand.

Not by chance, the world’s most renowned sovereign wealth funds such as the Government Pension Fund of Norway, Temasek and Kuwait Investment Authority invest heavily not only in their local AgriTech initiatives but in similar initiatives worldwide.

These savvy investors know that apart from a captive market AgriTech means efficiency and reduced risks with simultaneously increased yields. Yes, AgriTech is capital intensive, but it pays off.

Traditional notion of “self-sufficiency” is ironically, insufficient

The recent chicken supply shortage is a good example to show that even high self-sufficiency level (SSL) does not guarantee food availability. There are many elements beyond what is calculated for SSL that make the question of local production capacity, imports, exports and storage capacities (stockpile) to be insufficient parameters to consider when it comes to food security.

Malaysia’s chicken SSL is 113.5% according to DOSM based on 2020 data, but still, recently we faced a supply issue due to a combination of the following reasons:

- Higher prices and/or shortages of external inputs affecting output

- Short-term Government measures (price ceiling, export ban etc.) shut down smaller producers

- Potential withholding of supply from big players acting as a cartel to boycott Government measures

- Labour shortages

- Adverse weather conditions

Despite its high SSL levels, chicken supply experienced shortages and price increases.

Thus, high SSL is insufficient to guarantee food security with structural, economic and governance weaknesses.

It is also questionable how the stockpiling strategy for chicken would be successful given reports that existing storage capacities for fish failed to be utilised, resulting in similar shortage issues. The structural and governance issues still underline policy implementation weaknesses.

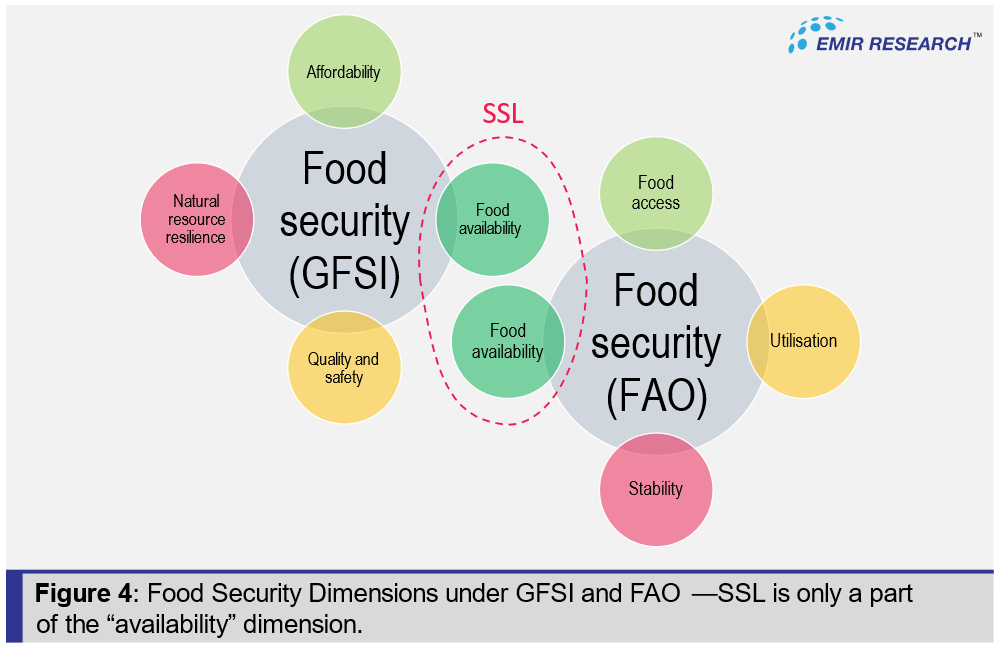

To be specific, SSL is only an element under one dimension (availability) of food security, which is a multi-dimensional issue. We can see this in the definitions outlined by both GFSI and The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) (Figure 4).

Past policies have not put focus on other crucial food security aspects, which would explain Malaysia’s poor score in environmental sustainability and jeopardise food safety, quality and nutrition.

For example, for climate change resilience, Global Food Security Index (GFSI) 2021 showed that Malaysia scored:

- 41.5% for the indicator “political commitment to adaptation” (100% being the most favourable food security environment). The global average score is 60.9%. This is a reduction of 3.8% from the previous year. Not only is Malaysia well-below average but it’s getting worse too.

- 0 out of 2 since 2012 for the indicator of “early warning measures/climate-smart agriculture”.

- 0 out of 2 since 2015 for the indicator “National Agricultural Adaptation Policy”.

- 1 out of 13 for the indicator “Commitment to managing exposure” indicator. The world average is 5.

For natural resources resilience, GFSI 2021 showed that Malaysia scored:

- 18.5% (ie. very weak) in the “oceans, rivers and lakes” indicator, which is critically below the world average score of 60.9%.

- 5 (the highest risk rating) for agricultural water risk, well above the world average risk score of 3.3, indicating serious water pollution.

The premise of national security is to assume the possibility of all scenarios and prepare accordingly. Therefore, we cannot take the climate, our natural resources, the weather and disaster risk profiles for granted. – June 29, 2022

Dr Rais Hussin and Ameen Kamal are part of the research team at EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.

The views expressed are solely of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Focus Malaysia.