I GREW up watching the hardest-working people I’ve ever known—my parents—build their lives with discipline, thrift, and remarkable resilience. They didn’t talk much about sacrifice. They lived it.

One of my fondest memories from childhood is the scent of spray starch on my father’s army uniform, particularly his No. 3 work dress, a light olive-green ensemble worn for daily duties.

Every morning, he’d iron it with military precision: sharp creases and clean lines. The scent of starch filled the air. It was oddly soothing.

It signalled structure (pun intended, as my father served in the Royal Signal Regiment), responsibility, and a quiet pride in serving something bigger than oneself.

Back then, hard work meant stability. Stability meant progress. That equation, however, doesn’t carry the same weight today.

When we overlook how the economic and social landscape has shifted, we risk misreading a fundamental change in values.

We all grew up in different Malaysias

My parents never asked for much. When my father retired from the military after 21 years, in a career he often summed up with quiet conviction as “Mati hidup balik sekalipun, aku tetap jadi askar”, he did so without much fanfare.

They simply packed up their belongings, left the army quarters and returned to their hometown where they bought their first home—a modest single-storey terrace house paid for with his equally modest pension.

Raising six children, they supplemented their income through long hours and hard labour. At the time, government pensions, community support, and frugality were enough to support a family of eight.

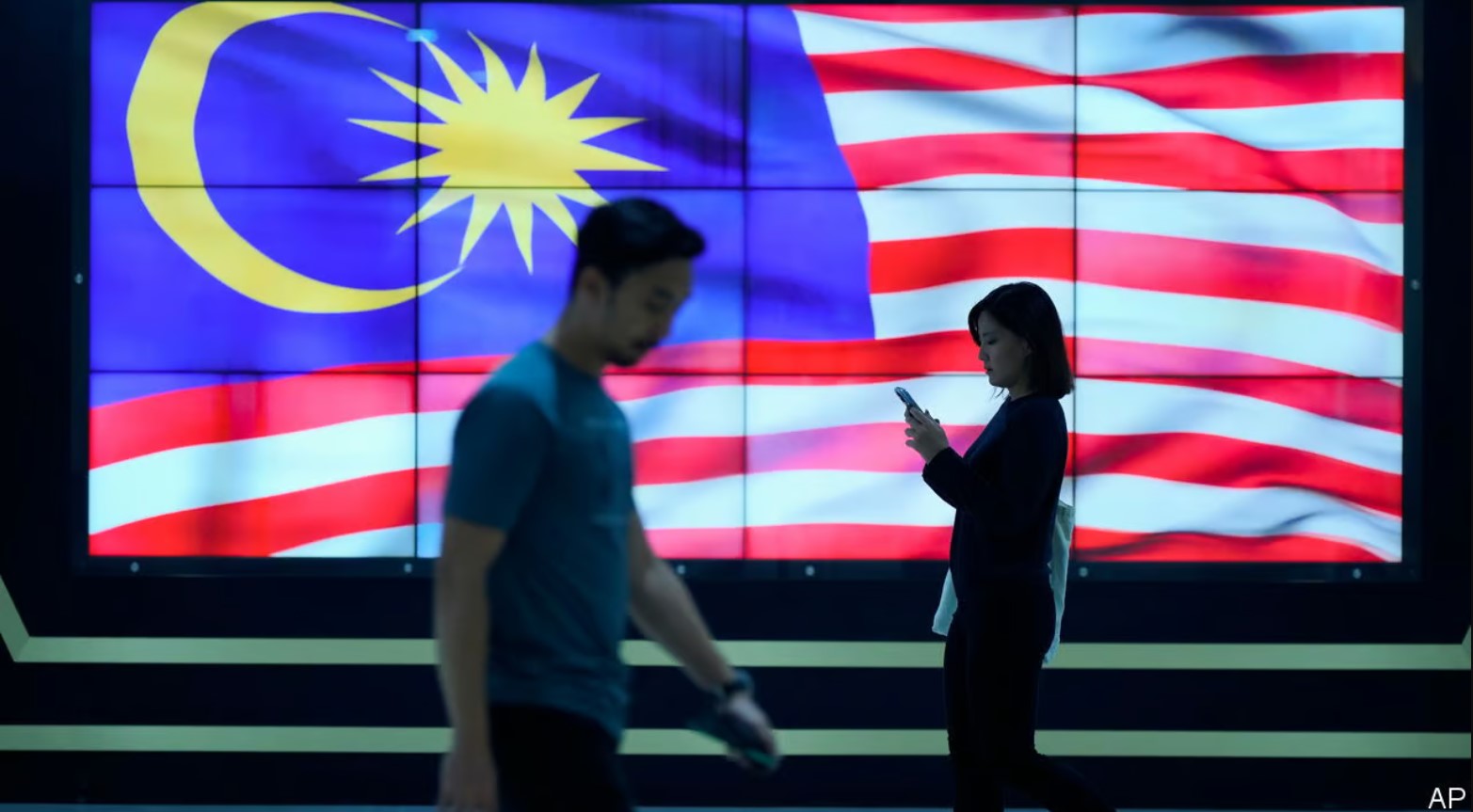

But the Malaysia they lived in is no longer the one young people face today.

Despite holding degrees and full-time jobs, many young Malaysians (the writer included) continue to struggle with home ownership, job security, and the rising cost of living.

According to the Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM), the median household income in 2022 was RM6,338 per month, or roughly RM76,056 per year.

Based on the global housing affordability benchmark, where a home should cost no more than three times the annual household income, a reasonably priced home in Malaysia should be around RM228,000.

In contrast, data from the National Property Information Centre (NAPIC) shows that the Malaysian House Price Index for the first quarter of 2025 stood at 225.3 points, with the average house price at RM486,070—more than double the affordable range.

Behind these figures are personal struggles and difficult choices. These are not just economic pressures, they are deeply human.

This isn’t entitlement. It’s adaptation. Different priorities, same worth

The generation that built Malaysia’s early economy placed immense value on order, loyalty, and seniority. In their time, these values aligned with a world where playing by the rules led to security.

Today, that promise may no longer holds. Even those who follow the ‘rules’, i.e., get a degree, secure a job, work hard, may still find themselves struggling.

As a result, today’s generation places greater emphasis on mental health, work-life balance, and meaningful engagement.

They speak openly about burnout and push back against outdated norms that equate long hours with dedication. They seek dignity, not just stability. Purpose, not just pay checks.

This isn’t a moral failing, but a reflection of a changing world.

In Islamic economic principles, fairness (‘adl), compassion (ihsan), and balance is key to a just society.

When times change, justice requires systems to adapt. What some may view as a lack of resilience is often structural strain, not individual weakness.

Shifting values don’t signal decline: they reflect reality.

From blame to building

Malaysia is ageing. By 2030, 15% of our population will be over the age of 60. At the same time, younger generations i.e., Gen Z and Gen Alpha will dominate the workforce.

Without mutual understanding, our social cohesion and economic vitality are at risk. Different generations have different concerns.

In the workplace, older Malaysians value punctuality and tenure. Meanwhile, the younger ones seek autonomy and flexibility.

National planning must evolve with the times. Our education, employment, and welfare systems need to reflect current realities, not just inherited assumptions.

For instance, Malaysia could introduce a centralised “portable benefits wallet” for gig workers, where contributions to retirement savings, healthcare, and social protection follow the worker—not the employer.

This model, already being piloted in the US and parts of Europe, ensures that contract and gig workers are not left behind in an economy where job security is no longer guaranteed.

Similarly, a Housing Start-Up Account for youth under 35, where the government matches a portion of savings—such as RM1 for every RM2 saved annually—could help first-time homebuyers overcome affordability barriers.

This approach, inspired by Singapore’s CPF model, would encourage long-term financial planning while making home ownership more attainable.

These kinds of forward-looking policies recognise that fairness looks different across generations. And, therefore, so does respect. – June 3, 2025

Dr Mohd Zaidi Md Zabri is the Interim Director at the Centre of Excellence for Research and Innovation for Islamic Economics (i-RISE), ISRA Institute, INCEIF University.

The views expressed are solely of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Focus Malaysia.

Main image: The Borneo Post