THE low voter turnout of 54.92% in the recent Johor election has set tongues wagging among politicians that the Election Commission (EC) is experiencing a trust deficit but no one really bothers to define what is meant by a low voter turnout.

Similarly, what constitutes a high voter turnout? Does it mean a 100% full turnout at the poll?

Politicians who talked about a trust deficit of the EC, coincidentally, came from the Opposition parties which gives the impression that they are more of sore losers rather than wanting to see the issue from an objective perspective.

A voter turnout of 54.29% means more than half of those who were eligible to vote turned out to vote, and hence you cannot describe it as a measly turnout as compared, for instance, with a measly voter turnout of 10% or less.

So the first order of business is to first find out what is the cut-off percentage of voter turnout that can be considered as low.

The table below shows the voter turnout for all general elections (GE) at the federal level, including the first one in 1955 held before Independence.

| Federal Election (Year) | Voter turnout (%) |

| 2018 | 82.32 |

| 2013 | 84.84 |

| 2008 | 75.99 |

| 2004 | 73.9 |

| 1999 | 69.3 |

| 1995 | 68.3 |

| 1990 | 72.3 |

| 1986 | 74.39 |

| 1982 | 75.4 |

| 1978 | 75.3 |

| 1974 | 75.1 |

| 1969 | 73.6 |

| 1964 | 78.9 |

| 1959 | 73.34 |

| 1955 | 82.8 |

Source: Let’s Talk! (Compile from various sources)

The highest turnout was at 84.84% recorded during GE13 in 2013 when Datuk Seri Najib Tun Razak was the prime minister (PM), while the lowest turnout was at 68.3% during GE9 (1995) when Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad was the PM.

Note that the average turnout (which is derived by adding the voter turnout percentages for all the 15 GEs and then dividing it by 15) is 75.72%.

If we ignore the first GE in 1955 because it took place before the country achieved Independence in 1957, then the average voter turnout is 75.21%.

But if we take the average of the highest (84.84%) and the lowest (68.3%) voter turnouts, the average turnout will be 76.57%.

From all these figures, we can say that anything that is below 60% is a low voter turnout; anything in the range of 60% to 80% is a reasonable voter turnout while above 80% is a convincing voter turnout.

Now, what does a low voter turnout mean? In general, low turnout is attributed to disillusionment, indifference or a sense of futility – the perception that one’s vote won’t make any difference.

Assuming that low turnout is a reflection of disenchantment or indifference, some analysts conclude a poll with a low turnout may not be an accurate reflection of the will of the people.

But it is questionable to say that a low voter turnout meant that the winner of the election did not “really win” as it does not in reality reflect the will of the people. This is hogwash that reflects the mentality of sore losers….where defeated candidates are in a denial mode.

In a democracy, the will of the people include their right to not to register for voting and the right of not voting even after registering for it. This is an internal contradiction of democracy with regards to the concept of freedom. It gives equal right to vote and otherwise in the name of freedom.

As long as the right to vote exists and there is no voter suppression such as when voters are not allowed or unable to vote, or when disenfranchisement occurs, the consensus on who is the winner as stipulated in the Federal Constitution reflects the will of the people, period!

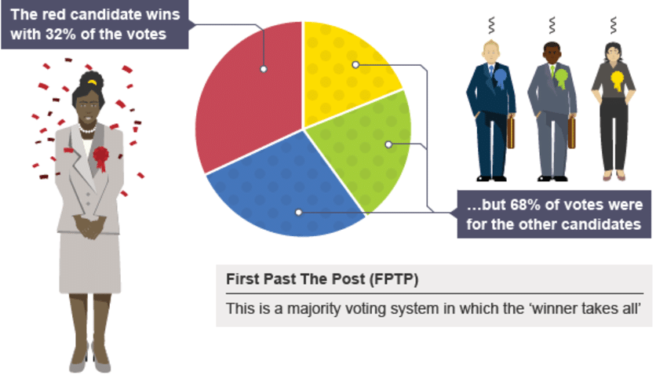

In Malaysia, we use the first-past-the-post (FPTP) principle which means that the candidate with the plurality of votes is the winner of the parliamentary/state assembly seat.

Even though the loser will have some voters voting for him or her, under the FPTP principle, it is a “winner takes all” system, as the winner is the one with the most number of votes.

That’s why in the 1987 UMNO election when Mahathir beat challenger Tengku Razaleigh Hamzah for the top spot by 761 to 718 votes (a mere 43-vote margin), the former was reported to have said a win is a win.

That’s the essence of FPTP principle – winner takes all, even if it is a win by one vote.

Of course, there will be cases when you add up the votes of all the winners and compare them against the votes of all the losers, the losers could end up with more votes than all the winners.

This is the concept of popular votes but the FPTP principle is primarily based on the number of seats won, not on the number of popular votes garnered.

Lower turnout a bane to the Opposition? Not necessarily

The Opposition would always say that low voter turnout is a disadvantage to them because it means many of their supporters did not turn up to vote.

This perception is based on the observation that when voter turnout is low, the Opposition will not only lose, but also sometime lose badly in the election.

But there have never been any studies done to show that the majority of voters who didn’t turn up for voting are Opposition supporters.

If we look at the figures on voter turnout above, the highest voter turnout in 2013 did not give an advantage to the Opposition at all because that election returned the Government back to office.

What is happening is that there is a correlation between low voter turnout and the Opposition losing is taken as a causal factor. In statistics and philosophy, correlation and causality are two different things.

This means that a low voter turnout can be consistent with both the Opposition winning or losing, just like it can also be consistent with the Government winning or losing.

Ditto with a high voter turnout

This is simply because high or low voter turnout is not the cause of winning or losing.

However, for both the winning and losing parties, the popular votes obtained could be important lessons on how they had performed during the election, and provide the clues on how to better perform in the next election.

A winning party that ignores the popular votes does so at its own peril. One cannot just focus on the number of seats won under the FPTP principle.

This is because the popular votes give an important clue on the voting pattern in each constituency, and even a rough idea of some demographic profiles of the voters in term of voting. For example, young versus old and rural versus urban, which will be a crucial factor in determining the winning strategy for the next election.

In 2008 for instance, the ruling BN for the first time failed to achieve a two-thirds majority and perhaps dismissed it simply because it had won the election.

Five years later in 2013, BN not only failed for a second time to get a two-thirds majority but also lost the popular votes to Pakatan Harapan for the first time.

However because of the FPTP principle, BN still won the election based on the number of seats won.

Again BN dismissed this second failure. Plus, they were arrogant when they dismissed the popular vote issue, saying a win is still a win. In 2018, BN had to pay dearly for this arrogance when it got voted out of office for the first time. — March 27, 2022

Jamari Mohtar is the Editor of Let’s Talk!, an e-newsletter on current affairs.

The views expressed are solely of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Focus Malaysia.