I AGREE with my former colleague at Univesiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM) Sharifah Munira Alatas that it does not make sense to talk about university students contributing to the growth of the nation if their role is subjected to oppressive laws such as the Universities and University College Act 1971 (AUKU) and other complementary laws and regulations.

Beyond the campus, there are plethora of laws that could be invoked to curb student activism if found “regime threatening”.

It is unfortunate that those who helm the higher education ministry can merely offer platitudes rather than seeing whether there is need to hang the sword of Damocles over the necks of students.

I surely agree that in this age of conservatism and racial-religious divide, the oppressive laws are basically an insurance to beget a passive behaviour on the part of students. In other words, a socialisation process to manufacture consent to those in power.

Gone are the days when university students rallied and protested against social injustices perpetrated in the country. The existence of oppressive laws are not the sole reason why there is lack of student activism in the campuses.

Climate of conservatism

If students are asked about their non-activism, they will invariably point out not just the AUKU but other laws and regulations that might be detrimental to their activism. In other words, it has become a self-fulfilling prophecy on the part of inactive students to blame the oppressive laws for their lack of activism.

Hypothetically, if these laws are removed overnight, I don’t think that students will suddenly jump into activism. While laws have a deterrent effect, they by themselves are not the sole reason why there is hardly any student activism in universities in the country.

The absence of student activism can be largely attributed to the long conditioning processes undertaken by regimes in power to ensure political stability and longevity. Manufacturing consent through the long process of hegemonic politics is a correct and sure way of ensuring regime stability.

In this respect, laws and other punitive measures of seeking compliance are necessary as a last resort but not the most effective way. In the words of Italian philosopher Antonio Gramsci, regimes intending to stay in power will not resort to repression but to build consensus or hegemony over a long period.

Hegemony refers to the consent people give to a political regime to stay in power. Similarly, if students are continuously oppressed to beget regime support, it might not serve the needs of the hegemony.

In the Malaysian context, there is a climate of conservatism among university students in not engaging in activism because they are subscribing to the hegemony of the regime. If students generally support the government in power through the hegemonic process, then why need the oppressive laws?

Passive students

Universities are not aloof from the larger society; in many ways, they represent the microcosm of the society. Just like the larger society, student politics in the universities have come to mirror ethnic and religious politics of the society.

Given the primacy of ethnic and religious politics in the campus, there are alignments either in favour of the government or in favour of the opposition.

As long as campus politics do not go beyond the ethnic and religious boundaries, the administration is happy not to intervene or regulate students’ activities by way of laws or regulations.

It is basically the manufacturing of consent for the hegemonic order that has prevailed in the universities. There is hardly any attempts to come together as students immaterial of ethnicity or religion.

Given the prevailing consent given by the students to the hegemonic order of the regime in power, student activism might not be there. Or alternatively, student activism might be artificially induced for regime support.

Even if the laws curbing student activism is removed, there is no automatic return to active politics among students.

It is this hegemonic order that slowly and surely manufactures consent to regime stability. At the same time, the process of consent serves as powerful antidote against students’ oppositional politics.

This conservatism among students in Malaysia is not unique to the country. The general decline of student activism across countries relate to how powerful ruling regimes have used sophisticated strategies to overcome dissent.

When ministers of the Madani government are going around urging students to play a critical role in the development of society, what they are essentially saying is that students should support the efforts of the government.

So much for student activism in Malaysia! – Oct 3, 2023

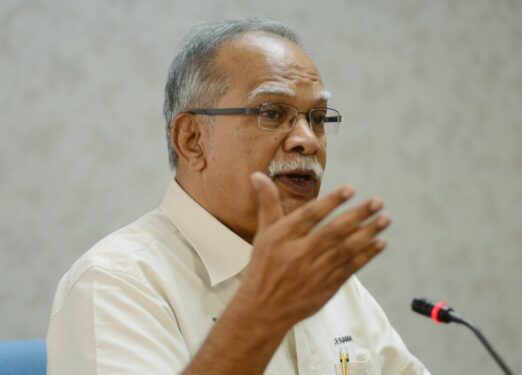

Prof Ramasamy Palanisamy is the former DAP state assemblyman for Perai. He is also the former deputy chief minister II of Penang.

The views expressed are solely of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Focus Malaysia.

Main pic credit: AskLegal.my