THE Chief Judge of Sabah and Sarawak, Datuk Abdul Rahman Sebli, was well within his rights in expressing his solitary disruptive dissent against the majority decision in the appeal brought up by Datuk Seri Najib Razak against various decisions of the earlier Federal Court panel of seven judges.

That is the lone judge’s prerogative which must be respected. That said, let’s recall the negative baggage of a bygone era of kakistocracy and kleptocracy.

The case involving Najib was an unprecedented one in that it involved a former prime minister (PM) as well as the country’s phenomenal wonder boy. He was the son of the country’s most powerful PM.

His father, Tun Razak Hussein, ruled the country by decree for more than a year after the May 13 incidents of 1969 and was responsible for overseeing legislation to extend the scope of Article 153 of the Malaysian Constitution which provides for the special position of Malays in the peninsula, to cover the natives of Sabah and Sarawak.

Razak died in office at the age of 53, and that sad reality provided Najib much mileage, sympathy and support which propelled his meteoric political career from his early 20s.

Criminal charges could only be levelled against Najib after he had vacated the PM’s office.

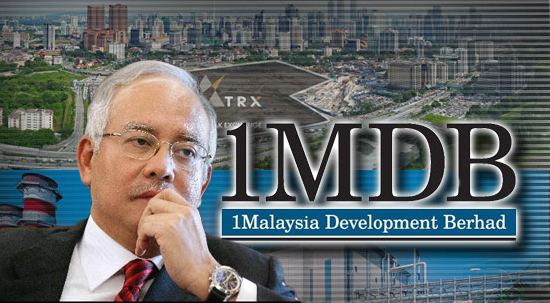

In his last three years in office, Najib was walking tall. He was effusive and upbeat about investing in the US and about Malaysia’s growth potential while being in the eye of the encroaching storm over the 1MDB (1Malaysia Development Bhd) debacle.

How it all began

However, the then US attorney-general (AG) Loretta Lynch made a damaging public disclosure on July 16, 2016 of the largest kleptocratic seizure which specifically related to Najib’s transgressions. Jeff Sessions, Lynch’s successor, called it “kleptocracy at its worst”.

On July 29, 2015, Najib had removed from their positions both the deputy prime minister and the Malaysian AG over differing perspectives on the 1MDB issue.

These episodes would show clearly that Najib was long in denial of the alleged embezzlement and misuse of public funds which could be easily traced to him.

When Najib lost the 2018 general election, he remained an MP who showed much determination to bring down and denigrate the fledgling Pakatan Harapan (PH) government.

On July 3, 2018, he was charged in court initially for three counts of criminal breach of trust and one count of abuse of power.

Proceedings at the High Court and the Court of Appeal moved in fits and starts as Najib’s legal team was able to raise reasonable grounds for postponements, adjournments and deferments on account of technicalities and other issues, including the COVID-19 pandemic.

After the completion of these processes over four years, the Federal Court comprising seven judges finally made its unanimous verdict, affirming his guilt, prison sentence and fine.

On Aug 23 last year, after some unusual courtroom drama involving a clearly dedicated but divided and dissembling defence team, Najib’s sentences which were passed initially at the High Court were reaffirmed. He was then taken to serve his 12-year prison sentence.

Najib was dissatisfied and his legal teams – the best that money could buy in the country – sought a review of those Federal Court proceedings.

Straightforward corruption case

The review panel made up of five judges, aware of their profound and sacred responsibility, delivered a 4-1 verdict dismissing Najib’s appeal on March 31, 2023.

Flash back five years ago. When a newly appointed AG Tan Sri Tommy Thomas appeared in court to lead the prosecution on July 3, 2018, he was duly authorised to act. More than that, he was the face and voice of the much-silenced whistleblowers, upright civil servants and innumerable people of Malaysia.

By the last years of Najib’s regime, acts of corruption, abuse of office and money laundering had grown rampant.

Contracts, franchises, licences, leases, monopolies, projects – including for major infrastructure – became the exclusive preserve of complicit corporate players. They appeared to be in cahoots with the agents, allies and associates of members of the country’s most corrupt and compromised government.

Najib’s was not an extraordinary case. It was a straightforward and typical corruption case. He took a relatively small payment of RM42 mil but the cost to the country in just that one case in monetary terms ran into the billions.

There was a larger, immeasurable, inestimable cost. For a small token sum, this holder of the most powerful office in the country was willing to sacrifice set safeguards, standards and the sanctity of trust.

He was willing to compromise on good and responsible governance which would impinge on the country’s sovereignty, security, well-being, integrity and international reputation.

He abdicated his sworn larger responsibilities to King and country for a pittance to maintain and sustain his elected position and affluent lifestyle.

Watertight judgment

The courageous people who spoke up against Najib from the beginning were the patriots, the loyal citizens, the whistleblowers and witnesses. They took immense risks and were prepared to face the consequences of squealing on the misdeeds of the most powerful official in the country.

Every step of the way, Najib – a popular and populist politician – could manipulate and organise shows of support for himself. He could sideline or sack his detractors or simply stonewall them.

Undoubtedly, Najib wielded almost unfettered power while in office but could not escape from the law. He became the accused in the high profile SRC International case.

There should not be any doubt that the process of investigating, gathering evidence, proceeding on the prosecution and hearing the case would have been done in the most impartial, meticulous and professional way.

Such care and caution were abundantly evident in High Court judge Datuk Mohd Nazlan Ghazali’s judgment. Those findings were watertight and could not be challenged or disturbed. For that reason, both the Court of Appeal and the Federal Court did not interfere with his findings.

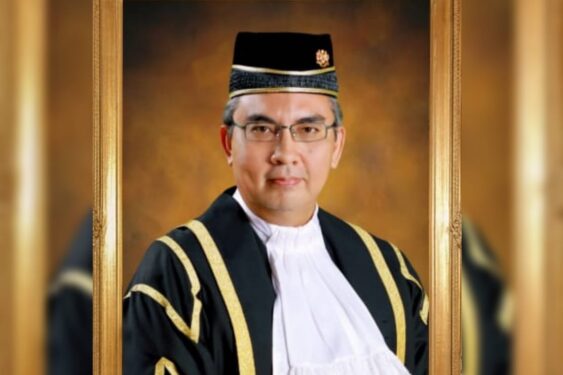

So, it does seem incongruent and somewhat impertinent that paragraph 115 of the dissenting judgment of Federal Court judge Abdul Rahman clearly implies that an order of discharge and acquittal of Najib would be the proper course.

It would seem Justice Abdul Rahman was unduly influenced by the defence’s submissions.

How could this have happened? – April 7, 2023

Datuk M. Santhananaban is a retired Malaysian ambassador with 45 years of public sector experience. His view first appeared in the ALIRAN portal under the heading “Defiant, Deficient and Deviant Dissent”.

The views expressed are solely of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Focus Malaysia.