IN September 2022, the MySejahtera application launched the “Organ Donor Pledge” registration feature to make it easier for Malaysians to sign up as organ donors.

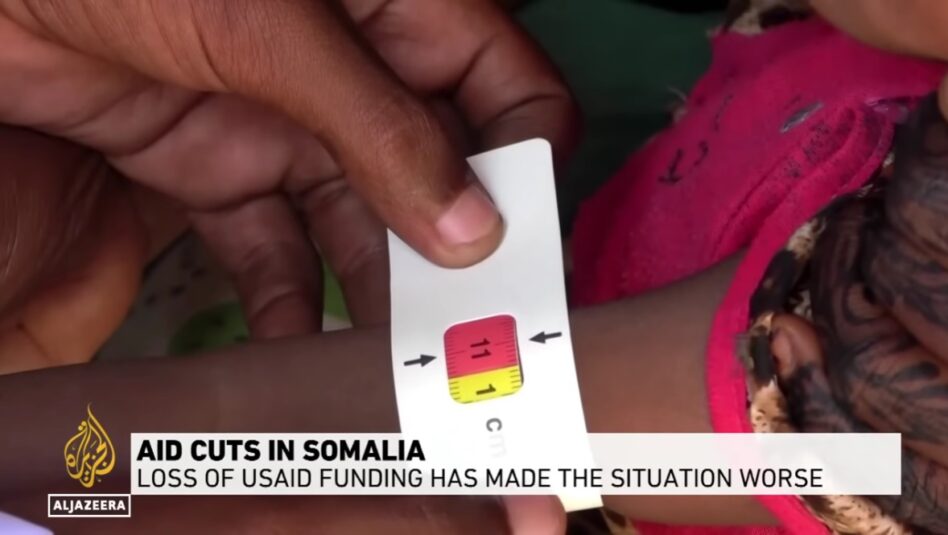

However, despite the government’s attempt to promote donor registration, the disparity between the demand and availability of human organs for transplantation in Malaysia continues to grow.

Former health minister Khairy Jamaluddin has stated that based on the Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation, Malaysia was among the 10 countries with the lowest organ transplant rates in the world in 2021, with 2.84 transplant procedures conducted per one million inhabitants.

Currently, Malaysia implements an opt-in system for organ donations, in which explicit consent from organ donors must be acquired prior to the removal of any organ.

As per the Malaysian Human Tissues Act 1974, a donor has to express his authorisation of the use of his body parts for medical purposes, medical research and education, either through writing or orally, in order for an organ donation to take place.

Despite the new feature introduced in MySejahtera bringing in more than 4,500 organ donation pledges, there have been controversial debates regarding the pledger’s consent due to the lack of information on the list of body parts the pledger consents to donate and digital signature.

This has brought Malaysia to discuss and examine the potential ethical and practical ramifications of Malaysia’s opt-out organ donation law in resolving the issue of low organ procurement rate while respecting donor autonomy.

In certain countries such as the UK, Spain, Belgium and Austria, the opt-out system has been adopted to increase organ donation rates.

Under the opt-out system, the default system presumes that a person consents to organ donation unless he explicitly registers his refusal. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), the opt-out system leads to higher donation rates.

Based on research from Northumbria University, the University of Stirling and the University of Nottingham on 48 countries’ organ donation systems (in which 23 adopted an opt-in system and 25 adopted an opt-out system), it was discovered that countries with opt-out organ donation regimes had a greater total number of kidney donations.

Reading the issue from the morality point of view, the increase of organ donation under the opt-out system is indeed a purposeful and altruistic act of giving, in which more lives are saved.

It represents the hope of survival in which “donating life” has become a significant means of sustaining life, restoring health and regenerating life: the opt-out system, bringing a significant contribution to the organ donation rate, reduces the number of patients suffering and dying while on waiting lists.

Not a magic bullet

However, the opt-out system is not a magic bullet, as donor autonomy has to be included in the big picture.

The opt-out system neglects the intention of the donor to donate his organ. This may lead to many organs being harvested without true informed consent, as consent is generally viewed as an active process and not as a result of inaction.

Such an opt-out system shifts the balance away from the donor’s interests and toward the donee, which creates a disproportion in the rights and liberty of the donor.

The fact that the opt-out system was repealed in Brazil only a year after it was implemented demonstrates the problems such a system would face, particularly on patient autonomy and when families were not permitted to overrule decisions.

Besides that, doctors are still permitted to remove organs even if relatives know that the deceased would have objected to donation but had not opted out during life.

These unresolved problems have shown that the opt-out system is not the absolute answer to address the low organ procurement rate in the country.

In the authors’ opinion, implementing an opt-out organ donation system or passing opt-out legislation is insufficient to increase the organ donation rate in the country. The opt-out law in Malaysia is undoubtedly too presumptuous in neglecting donor autonomy and will not solve the organ scarcity crisis.

On the contrary, the opt-out paradigm will simply create a moral and autonomy imbalance for patients.

The new feature in MySejahtera is a promising start; only a few details need to be refined before the issue of Malaysia’s low rate of cadaveric organ transplants can be rectified.

The government should improve the underlying infrastructure for transplantation under the opt-in system in order to boost income and investment in health care, as well as to eliminate the social stigma and religious and cultural beliefs that plague the public. – Nov 24, 2022

Evien See is a law student at Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM) while Dr Nabeel Mahdi Althabhawi is a senior lecturer attached to the public varsity.

The views expressed are solely of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Focus Malaysia.

Main photo credit: SoyaCincau