By Associate Professor Brian Imrie and Jon Knott

MALAYSIA is forging an international reputation as a major player in the renewable energy space – as both the largest Asean solar photovoltaic (PV) industry employer, and through setting an ambitious renewable generation target of 20% by 2025.

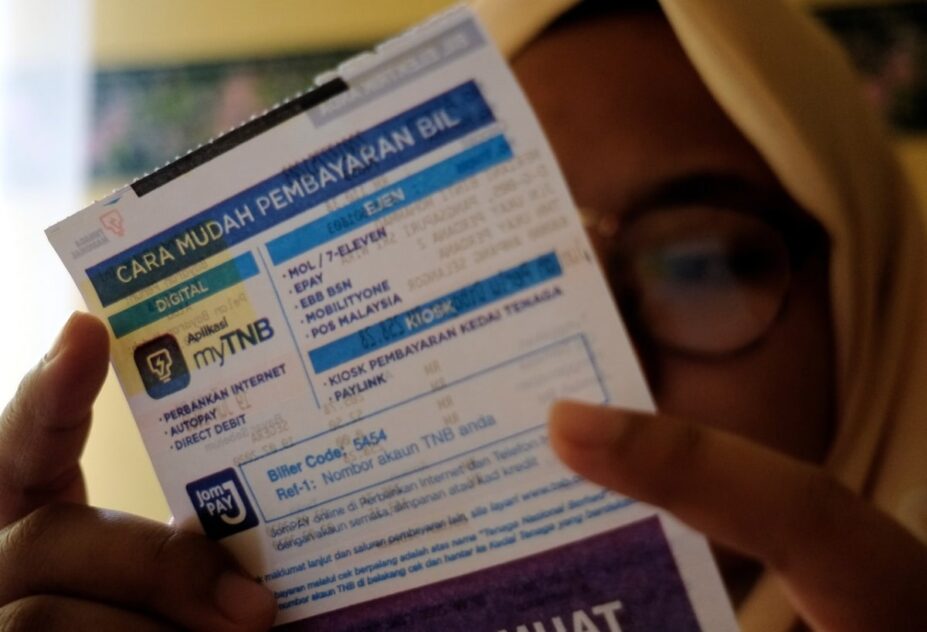

With approximately 3.2 million landed houses, 450,000 shop lots, 21,000 standalone factories and 1,000 shopping complexes – there is a substantial amount of roof top area that can be used to participate in Malaysia’s renewable energy revolution.

As Malaysia, and indeed the world, transitions to relying more heavily on renewable energy generation technologies for their electricity needs, a range of opportunities for battery-based energy storage are opening up.

The most obvious use of batteries is to provide back-up power during a blackout, but helping consumers with rooftop solar panels capture and use their self-generated electricity – rather than sell it to the grid – is also becoming more economically viable in places where the electricity costs are high.

Industrial users can also deploy batteries to help them deal with spikes in their power demands, which can make up a significant part of their monthly electricity bill. Utilities can also use batteries to smooth the output of large solar or wind farms, and to provide power quality services to their customers.

While lithium-ion batteries are currently being deployed in a number of these applications and more – including handheld electronics and electric vehicles – there exists opportunities for the development of novel energy storage materials and solutions to address some of these ever-growing needs.

To address some of these opportunities, a team from the University of Wollongong’s Institute for Superconducting and Electronic Materials (ISEM) are leading an international consortium of partners in an AUD$10.5 mil Australian Renewable Energy Agency-funded project to develop sodium-ion batteries for use in renewable energy storage applications.

Sodium-ion batteries share a number of similarities with their more well-known lithium-ion cousins. However, they also hold promise for the additional benefits that make them attractive for renewable energy storage applications.

Notably, the input materials for sodium-ion batteries are more abundant and typically cheaper than those for lithium-ion batteries. In addition, sodium-ion batteries don’t use cobalt in their architecture, which is one of the key issues facing lithium-ion batteries today.

The team at ISEM are working closely with an international consortium of industry partners to translate sodium-ion battery research successes into commercial demonstrations. Sydney Water – one of Australia’s largest water utilities – is a key part of the consortium and will demonstrate the consortium-developed sodium-ion batteries in one of their 780 sewage pumping stations.

The Illawarra Flame House – which won the 2013 Solar Decathlon China competition and is now a ‘living laboratory’ at UOW’s Innovation Campus – will also host a sodium-ion battery pack, showing how this technology could also be of benefit in residential energy resilience and self-consumption applications. – April 4, 2021

Associate Professor Brian Imrie is the deputy vice chancellor (Engagement) of UOW Malaysia KDU and Jon Knott is a research fellow at University of Wollongong’s Institute for superconducting and electronic materials (ISEM).

The views expressed are solely of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Focus Malaysia.