THERE was a spike in intergroup conflicts and acts of intolerance leading up to the 2018 general elections and during Pakatan Harapan’s first year in power, with the coalition partly at fault, a research study stated.

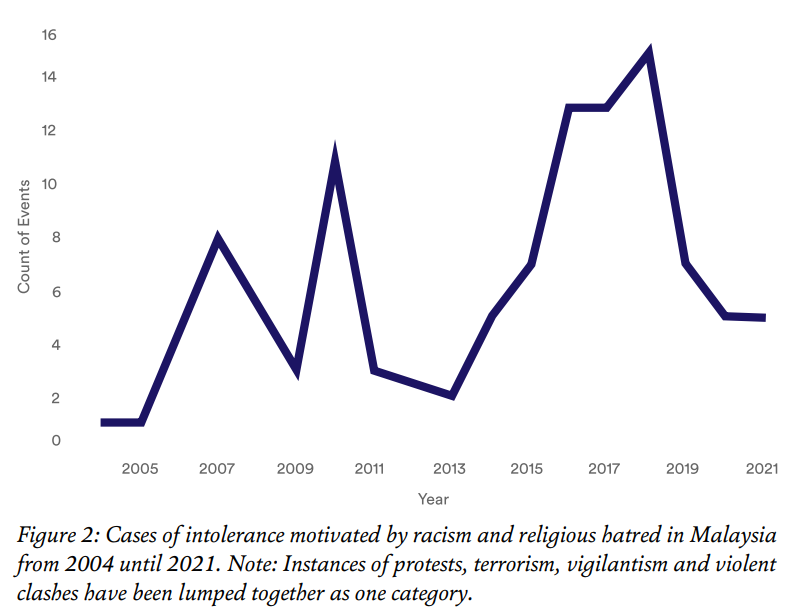

According to an Initiative to Promote Tolerance and Prevent Violence (INITIATE.MY) policy brief published yesterday, instances of protests, terrorism, vigilantism and violent clashes increased from 2017 to 2018 after a two-year “lull”.

These cases of intolerance, motivated by racism and religious hatred, peaked around May 2018 when the elections were held, with major cases reported for the rest of the year, the research group observed.

“Drivers of this trend may include reactions to the Pakatan Government’s introduction of institutional reforms and its failure in managing intergroup conflicts,” INITIATE.MY project officer Hisham Muhaimi said in the policy brief entitled, “Holistic Recommendations to Tackle Hate Speech, a Driver of Intolerance in Malaysia”.

This trend, he added, was complemented by Malaysia’s 2018 and 2019 “warning” rankings on The Fragile States Index, a tool that assesses a country’s vulnerability to conflict or collapse.

However, Hisham noted that cases “rapidly declined” in 2019, and decreased in the years that followed, likely due to the change in Government and movement control orders.

The Pakatan Government fell in March 2020, and Malaysia went into a lockdown shortly after.

Hisham cited several incidents from 2018 and 2019 to make his case, such as the Sri Maha Mariamman Seafield temple riots, the mammoth anti-International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD) rally and the opposition to the introduction of Jawi khat calligraphy in vernacular schools.

“Based on INITIATE.MY’s analysis, hate speech and misinformation were among the main drivers in most of these cases,” he wrote.

“Fear and anger were instigated based on existing narratives that were against minority groups or in support of the majority race’s supposed supremacy.

“Such sentiments were then amplified in online and offline spaces to mobilise followers of religious and political actors into participating in protests, boycotts and in some cases, violence.”

Irresponsible politicians

The anti-ICERD groups, for example, believed that ratifying it would infringe on the special privileges accorded to the bumiputeras and pose a threat to the position of Islam.

“These narratives, however, were unfounded,” Hisham pointed out. “For instance, ICERD Member States are able to make reservations about special rights or affirmative actions.”

Regardless, media content was pruned to claim otherwise, besides pushing out racially-toned narratives against non-Malays and ICERD supporters – branding them as “immigrants” and “traitors” to the country, for instance.

Similarly, messages, posters and footage painting the Seafield temple riots as a racial clash between the Malays and Indians circulated on social media like hot cakes, with “irresponsible actors” trying to politicise the incident as well.

“Certain leaders made racist statements on the issue, including Jaringan Melayu Malaysia president Azwanddin Hamzah, who used a derogatory word against an Indian minister in the Pakatan Government three times at a public rally,” Hisham noted.

The study also noted that politicians were equally guilty of mobilising support for these causes. Hisham made reference to a fatwa by PAS president Tan Sri Abdul Hadi Awang who urged Muslims to take part in an anti-ICERD rally as part of their “religious duty”.

On that note, Hisham called for lawmakers from both sides of the political divide to work towards reforming existing laws like the Sedition Act 1948 and Communications and Multimedia Act 1998 so that hate speech could be tackled holistically.

“For a start, these laws should provide a clear mandate to enforcement authorities like the police and Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC) to tackle provocation from the start and empower victims to lodge reports to the authorities to seek justice.

“This can be done by defining and protecting minority groups under these laws, and making incitement towards such groups an offence.”

Besides protecting minority groups and society at large, Hisham opined that such reforms will also play a major role in disallowing the politicisation of race and religion, “of which politicians themselves are arguably the usual perpetrators”. – July 16, 2022