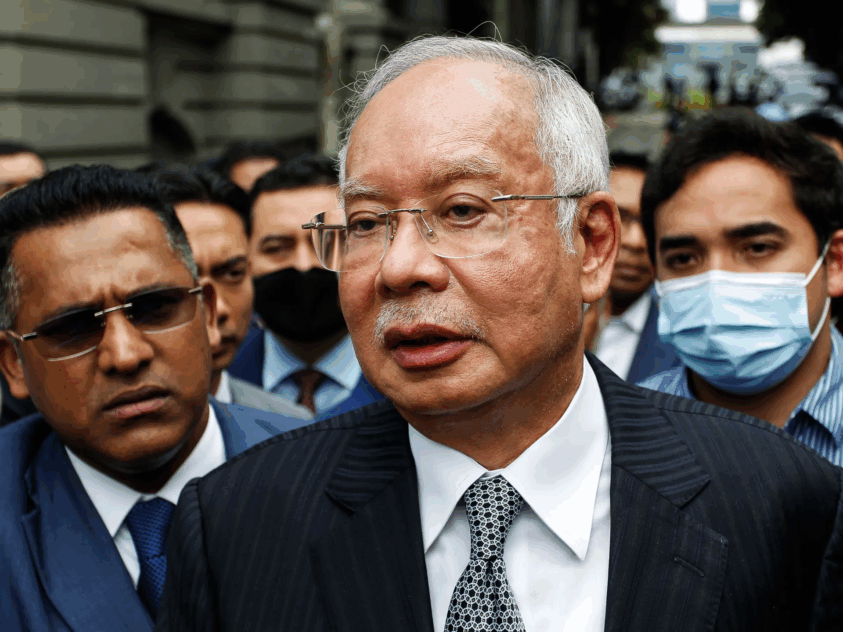

IT IS human and natural that we remember the good deeds of Malaysia’s fifth Prime Minister Tun Abdullah Ahmad Badawi—fondly known as Pak Lah.

His ascension to the premiership in 2003, following the resignation of Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad, was seen by many as a breath of fresh air.

After more than two decades of Mahathir’s assertive leadership, Malaysians appeared ready for a softer, more inclusive approach.

Pak Lah, with his calm demeanour and unassuming nature, seemed to be the right man at the right time. He was neither flamboyant nor confrontational, but rather moderate and measured—a stark contrast to his predecessor.

Mahathir, perhaps cautious after his fallout with former deputy Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim, chose Badawi as a successor he believed would continue his legacy. However, that expectation proved misplaced. While Badawi respected the structures he inherited, he had his own style—gentle yet firm, calm but not passive.

He was no pushover. Yet, he also never engaged in open conflict with his ever-watchful predecessor. Instead, Pak Lah quietly introduced reforms in his own understated way.

One of his key initiatives was Islam Hadhari, a progressive and pragmatic approach to Islam that emphasised development, knowledge, and ethics—well-suited for Malaysia’s multi-ethnic and multi-religious society.

It was an attempt to present Islam not as a divisive force but as a framework for good governance and inclusivity.

While his tenure was not without criticism—particularly over allegations of nepotism and the use of the Internal Security Act (ISA) against leaders of the Hindraf movement in 2007—these issues were modest compared to the widespread corruption and abuse that plagued other administrations.

The detention of Hindraf leaders, although regrettable, occurred amid intense pressure from the police following mass demonstrations. Nonetheless, it marked a turning point.

In the 2008 general elections, the Indian community abandoned the Barisan Nasional (BN) in large numbers, followed closely by the Chinese community. The opposition’s unprecedented success led to the fall of five states and signalled a seismic shift in Malaysian politics.

Pak Lah was not a maverick or radical reformist. He did not seek to uproot the political system or redefine Malaysia’s direction. But he also did not pander to racial or religious extremism.

In an era when some politicians capitalized on identity politics to gain support, Pak Lah chose a different path. He valued national unity based on tolerance and mutual respect.

Despite his moderate approach, his impact was real. He implemented administrative reforms, including measures to improve public service delivery and combat corruption.

Under his leadership, the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission (MACC) was established, and efforts to modernize the civil service were introduced.

Perhaps the most humbling and admirable aspect of Pak Lah’s career was his humility. He never sought to glorify himself or wield power for its own sake.

He accepted the limitations of his role, working within the system he inherited, and chose not to weaponise race or religion for political gain.

While he didn’t promise the heavens, Abdullah Ahmad Badawi left behind a legacy of moderation, simplicity, and quiet dignity.

His leadership style may not have been loud or revolutionary, but it helped shape a more tolerant and humane political environment—something Malaysians can still look back on with a sense of gratitude. – April 17, 2025

Former DAP stalwart and Penang chief minister II Prof Ramasamy Palanisamy is chairman of the United Rights of Malaysian Party (Urimai) interim council.

The views expressed are solely of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Focus Malaysia.

Main image: Malay Mail