IT has been reported that Prime Minister Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim’s visit to Thailand this Thursday (Feb 9) might add some impetus to the peace process between the Thai government and the Thai Muslim rebels.

Anwar’s visit is preceded by the visit of the Malaysian chief facilitator, former army general, Tan Sri Zulkifli Zainal Abidin. Zulkifli replaced the former chief facilitator, Tan Sri Abdul Rahim Noor, who was named for this role in 2018.

Abdul Rahim was the former inspector general of the Malaysian police who was appointed the facilitator in 2018.

Like other peace processes in the region, the Thai-Muslim conflict goes back to the 1940s when the Thai government annexed the region of Pattani that had predominantly Malay-Muslim population.

The conflict flared up in 2004 and until today 7,000 lives have been lost. Presently, apart from negotiations now and then, there are signs that a permanent peace is possible in the restive provinces of Ayala, Narathiwat and Pattani.

After much ambiguity as to representatives of the Thai-Muslims, the emergence of Barisan Revolusi Nasional (BRN) gave some clarity to the peace process.

Finally, there appeared on the scene a collective representative of the Thai-Muslims in the form of BRN.

However, a clear and unambiguous representation seems to be defying element of the entire peace process.

Thai Muslim unity

Even if the BRN is the strongest representative of the Thai-Muslims, it has no sole monopoly over the fighting forces.

The peace process doesn’t take coherence because of the presence of other groups that are bent on thwarting the peace process.

Each time some gains are made in the negotiations between the Thai government and BRN, there are centrifugal forces out to derail negotiations.

Unlike other former prime ministers, Anwar given his exposure and understanding of the regional issues, might lend credibility to the peace process.

There is a possibility that his role might persuade the Thai-Muslim groups to coalesce under one political umbrella rather than being divided. BRN might be revitalised with the moderating role of Anwar.

But then, the very process of consolidating the different Thai-Muslim factions under one effective representation lies within the Thai-Muslim society particularly the members of the civil society.

However, even if Anwar gives some encouragement to the peace process, the fact remains that the conflict is between the Thai-Muslim separatists and the Thai government.

The ultimate solution to end the long-drawn-out conflict depends on the progress made by the two parties on the negotiating table.

Malaysia with the presence of Anwar is a mere externality to the conflict. It can only perform the role of a mediator or facilitator. The very definition of such role is limited in scope.

The country has to adopt a neutral role because the Thais might be suspicious if Malaysia displays some elements of sympathy for the Thai-Muslim cause.

Walking on thin ice

Of course, as far as Malaysia and Thailand are concerned, a separate state for Thai-Muslims is out of question. While Thailand is firm against independence, Malaysia might not favour such an option.

Independence for Thai-Muslims might encourage the problem of irredentism given the close ethnic, cultural and religious ties between Malay Muslims on both sides of the border.

Not the least, the ASEAN spirit forbades any thinking on independence as it would be construed as a gross form of interference.

Anwar can use his charm to take the peace negotiations to another level. The conflict is far from over.

Ultimately, the success of the peace process will depend on the two parties – Thailand and the Malay Muslim rebels. Malaysia might not have direct role.

Malaysia as the facilitator has shown much concern in ending the long years of the bloody conflict. But there are obvious limits.

Malaysia might not be really a neutral party; domestic championing of race and religion might arouse the suspicions of the Thai government.

To what extent Thailand believes that Malaysia can facilitate the conflict to a successful end remains to be seen.

Malaysia’s biggest headache is how to unite the myriad rebel groups under one political umbrella. BRN might not be the best example; it cannot control events outside its grip.

How serious is Thailand in finding a speedy solution to the conflict? The demographic changes fast happening in favour of the Thai-Buddhist population might be to the advantage of the Thai government.

There are very few separatist conflicts in the world; the struggles of the Thai-Muslims and the Papuans of Papua Barat are the few examples in Southeast Asia.

There are suggestions that Malaysia given its close ties with the Thai-Muslims might not be the appropriate or neutral party in facilitating the peace process.

Alternatively, it is suggested that neutral party be appointed not as the facilitator but a mediator to the conflict in the restive Thai-Muslim provinces.

Here the role of Finland in successfully mediating the conflict between the Free Aceh Movement (GAM) and the Republic of Indonesia (ROI) in 2005 comes to my mind. I was one of the advisors of GAM. – Feb 6, 2023

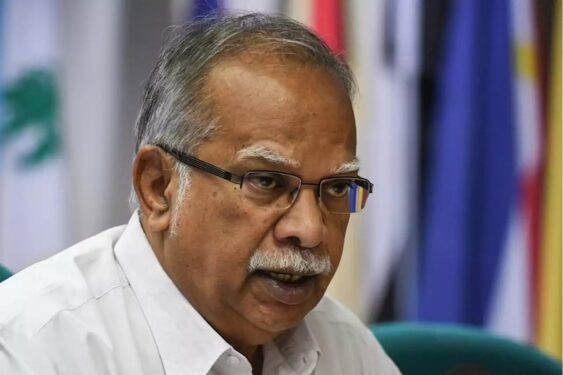

Prof Ramasamy Palanisamy is the state assemblyperson for Perai. He is also Deputy Chief Minister II of Penang.

The views expressed are solely of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Focus Malaysia.

Main pic credit: The Nation