THE ICT Use and Access by Households Survey Report 2021 released by the Department of Statistics (DOSM) has reported that Internet usage in Malaysia last year increased by up to 95.5% compared to 91.7% in 2020.

However, as internet access has become more widely available, this has made room for paedophiles to sexually abuse children through virtual means such as grooming and accessing child pornography.

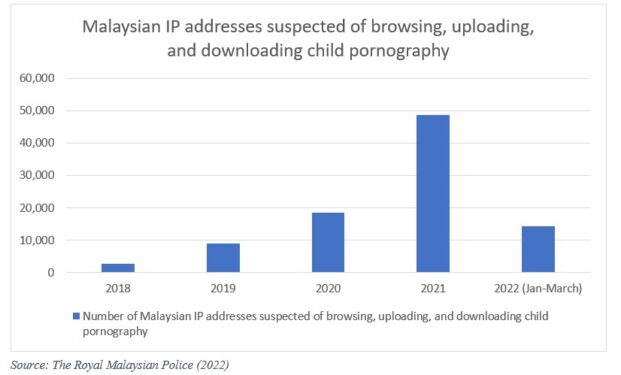

As reported by the Royal Malaysian Police’s (PDRM) Sexual, Women and Children Crime Investigation Division (D11) Principal Assistant Director ACP Siti Kamsiah Hassan, data shared by Interpol, FBI, and National Centre for Missing and Exploited Children showed that from 2017, there were only 46 IP addresses identified.

By the year after, i.e., 2018, however, the number has spiked to 2,660 IP addresses and it kept increasing dramatically afterwards – escalating to 48,752 IP addresses in 2021.

In total, there were 93,368 IP addresses detected engaging in cyber-paedophilia activities from 2017 until the first quarter of 2022.

Nevertheless, it is not surprising that the number of IP addresses accessing child sexual contents online could continue to rise.

This by itself should incite us to think as to how we could do more to suppress cyber-paedophilia that represents a real and present and continuing danger to children not only outside but in Malaysia also.

The discovery of two notoriously well-known paedophiles – one based in the country and the other via cyberspace, namely Richard Huckle and Blake Johnston, respectively – finally led to the introduction of the Sexual Offences Against Children Act (SOCA) in 2017.

However, even after the Act was passed, it was discovered in 2018 that Malaysia had the largest concentration of IP addresses used to upload and download child pornographic content in Southeast Asia.

Why does the number of Malaysian IPs addresses continue to be high?

First, the current legislative provisions in Malaysia pertaining to online child sexual exploitation have some limitations.

The SOCA (2017) is a comprehensive legislation that seeks to safeguard children from both online and offline sexual abuse compared to the older Child Act (2001) that does not criminalise child pornography.

In spite of that, Ecpat International (a global network of civil society organisations that works to end the sexual exploitation of children) has scored Malaysia 0/100 in the Out of the Shadows indicator for internet protection for children.

This is because ISPs (Internet service providers) in Malaysia were not obligated to block, delete or report inappropriate information concerning child sexual abuse.

Moreover, directives by the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC) can only go so far, since the any blocking of access is limited to the Domain Name System (DNS) or IP address which can be easily circumvented.

Secondly, PDRM is under-staffed and not well-equipped to effectively combat and deter child pornography online.

ACP Siti Kamsiah Hassan stated that the reason why the number of arrests is very low is due to manpower shortage and not enough trained staff in digital forensic training, including to filter and track the IP addresses, despite having the technical apparatus to do so.

In reality, PDRM relies heavily on information and data shared by international counterparts and partners.

In early 2022, only 103 out of 14,385 IP addresses were tracked leading to the arrests of 50 individuals.

These IP addresses come under the purview and review of the PDRM’s Malaysian Internet Crime Against Children (MICAC) D11 investigation unit which at the moment only comprises of three investigating officers (IOs) who are all ranked inspector.

Additionally, despite having the technical apparatus, PDRM has said that the Data Protection Act (2010) has made it more difficult for them to have full access to the activities from the IP addresses.

For example, whilst PDRM can track the IP addresses, at present they are unable to determine whether any sharing or exchanges of images and videos have taken place.

According to PDRM, this is because private activities carried out within the (public) internet domain are protected under the 2010 Act which hampers the effectiveness of the ICACCOPS, i.e., the technical apparatus or software deployed to detect the IP addresses.

ICACCOPS stands for Internet Crime Against Children: Child Online Protective Services.

Thirdly, the social stigma built around the topic of sex has led to under-reporting.

The taboo and shame surrounding sexual abuse topics/issues contribute to the lack of awareness among some minors which in turn increases their susceptibility/vulnerability to sexual exploitation.

There is also the sub-culture whereby the perverted fascination with child and pre-pubescent sexuality is considered as a trivial and minor issue. – Aug 22, 2022

The story continues in Part 2 – Cyber-paedophilia in Malaysia: Ensuring pro-active role for ISPs.

Jason Loh and Nik Nurdiana Zulkifli are part of the research team of EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.

The views expressed are solely of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Focus Malaysia.

Main pic credit: MIT Technology Review