I REFER to recent articles on these plant nurseries under power transmission lines, in particular Focus Malaysia’s coverage of this issue.

Legalised secondary use of infrastructure land is good as long as it does not compromise public safety and helps to preserve green corridors. It helps to build community vigilance against ‘idle land’ falling prey to encroachment, misuse and misappropriation.

Most people are aware of Temporary Occupation License (TOL) as a means of gaining legitimate rights to use government (‘state’) land on condition of not violating building control laws.

Permanently Reserved Forest (PRF) as the National Forestry Act (NFA) calls it has a different version of ‘TOL’ called Use Permit (UP). Like its state land cousin, it also needs to be renewed annually on the calendar year, i.e., Jan 1 to Dec 31.

Media reports consistently point to these Tropicana Selatan nurseries having been administered by the Selangor Forestry Department (JPNS) for years if not decades.

The traverse of utilities across PRF land is not limited to electrical transmission corridors, and does not affect its legal status as PRF, with (other) laws providing the ‘Right of Way’ (ROW).

I personally saw and photographed UP signboards and sighted permits with expiry dates as recent as Dec 31, 2021. So, it is slightly over three years now since JPNS stopped entertaining renewal applications.

Does this mean the land suddenly lost its PRF status? Has jurisdiction transferred to the Petaling District and Land Office (PDTP)? Or is the land still under JPNS who are no longer willing to issue UPs?

A letter from JPNS’s state director dated April 29, 2022 informing a nursery operator of non-renewal of UP was appended in V. Thomas’ Jan 9 article.

It went on to purport that the land had reverted to being state land since 1991 (“telah disytiharkan melalui Sl. PW307-91”).

This is irregular, and begs the question: why did JPNS continue to administer it for another three decades? Shouldn’t the nurseries have obtained tenure via TOL instead, from the PDTP?

One thing is for certain: such jurisdiction transfer is not something to be decided among civil servants at departmental level. Excisions of PRF are decided by the state authority i.e., the Menteri Besar chairing the Exco, taking effect on the date of publication in the Gazette (Warta Kerajaan Negeri Selangor).

Instances of left and right hand not knowing what each other is doing are not uncommon. However, it feels quite improbable that such omission could have remained undetected for three decades.

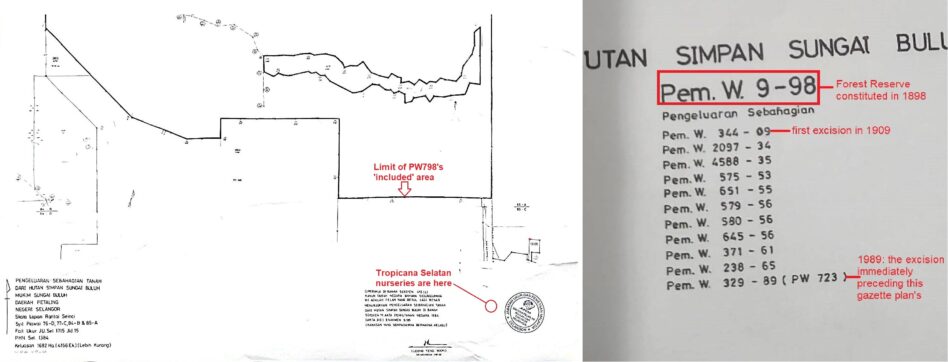

To help demystify this I procured plan PW798 from the Survey Department. A definitive ‘overlay’ on Google Earth shows PW798’s area terminating on the opposite side of the SPRINT highway, placing these nurseries some 600 metres away.

This plan is now with one of the nursery owners to facilitate his follow up action, which should start with asking JPNS to double check and verify their basis for claiming to no longer be able to renew UPs.

Giving benefit of doubt, it may be possible that JPNS misquoted the plan number and year of excision. All the nursery operators should band together to collectively seek out the facts for an informed course of action.

“Sl. PW307-91” was among the most sizable on the excision chronology, and was for developing the township of Kota Damansara. During that period, it was fairly straightforward for the state to excise forest reserves without public knowledge.

A 2011 Amendment to Selangor’s National Forestry Act (Adoption) Enactment changed that, by requiring ‘the holding of a public inquiry’.

A case currently before the courts—Damien Thaman Divean (Mewakili Pertubuhan Pelindung Khazanah Alam) & Anor v Majlis Eksekutif Negeri Selangor Darul Ehsan (Exco) & Ors—challenges the state government’s excision, without public inquiry, of 1,000 acres of Bukit Cherakah Forest Reserve via a 2022 gazette citing an Exco decision made 22 years earlier, i.e., before public inquiry law came into effect.

This dubious backdated referencing of “Sl. PW307-91”, unless corrected and clarified, could likewise erode public confidence in the administration of forestry laws.

The bottom line is that PRF cannot be directly alienated to private ownership—excision and transfer over to land office administration must happen first.

Whereas on state land, TOLs can be summarily terminated to alienate and give vacant possession to a new landowner as has already happened in KL’s Taman Bukit Desa after overhead lines were re-installed (buried) underground.

I thoroughly agree with V. Thomas that the substantial TNB transmission reserves in the Klang Valley and elsewhere can be put to good agricultural use.

Ecological corridors are key to a sustainable urban fabric—not of one city but of our National Conurbation, a term used by town planners for Malaysia’s largest urban centre spanning more than half a dozen city/municipal councils.

Power transmission corridors are not only farmable for food, they are significant among the ‘ready-made arteries’ for sustainable urbanisation. – Feb 26, 2025

Peter Leong took an interest in environmental conservation and urban sustainability issues after retiring from an engineering career in the petroleum industry. He has previously served on the committees of two green lung community-based organisations, remaining an active volunteer while acting as freelance researcher for a number of civil society organisations.

The views expressed are solely of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Focus Malaysia.

Main image: The Star