MOST babies seem small when they first come into the world, but for some, they truly are smaller when compared to their fellow babies-in-arms.

This condition, known medically as small for gestational age (SGA), is one that can be measured objectively, and indeed, such measurements are done as a matter of routine for all babies born in Malaysia and across the world.

After birth in a hospital or clinic, the nurses are not only cleaning and giving them a quick check for any abnormalities, but also measuring their length and head circumference, and weighing them.

These three measurements are the ones that are able to inform healthcare professionals whether or not a baby is small for its gestational age (defined as the length of time a baby spends growing in its mother’s womb).

SGA can be categorised as preterm or term. Preterm refers to babies who are born before 37 weeks of pregnancy are completed, while term babies are those who are born at or after 37 weeks of pregnancy.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), SGA babies are those whose weight and length fall below the 10th percentile of the growth chart for their gestational age.

For babies born at term, there is an additional criterion – ie whether their weight at birth falls above or below 2,500 grams (SGA babies who weigh below 2,500g at birth are additionally considered to have low birth weight).

Causes of SGA

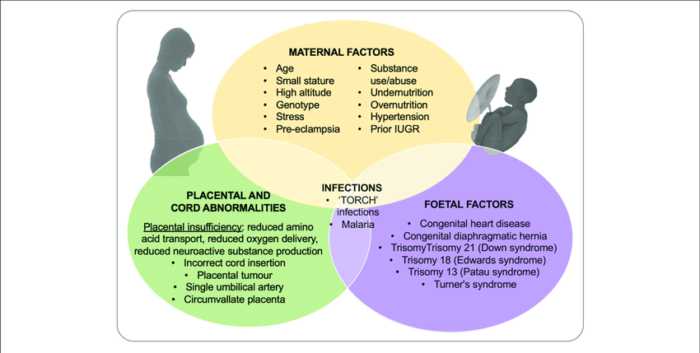

There are three main causes of SGA: maternal, placental and fetal.

- Maternal

Maternal causes include the mother’s health during pregnancy (eg if she had any infections or medical conditions such as heart disease or uncontrolled diabetes, thyroid disease or high blood pressure during that period).

Drinking alcohol or smoking, as well as poor nutrition, during pregnancy can also result in an SGA baby. Other factors include the age and height of the mother.

The risk of having an SGA baby is significantly higher for women aged 30 and above who have never given birth before, as well as all women aged 40 and above, compared to women in their 20s.

Women who are short are also at risk of having an SGA baby due to anatomical reasons; their smaller wombs and shorter birth canals influence the growth of their fetus.

Interestingly, research has shown that the risk of having an SGA baby can be influenced as far back as two generations. This means that if the pregnant woman, or even if their own mother (the fetus’ grandmother), were SGA babies themselves, the fetus has a higher chance of being born SGA.

- Placental

Placental causes include placental insufficiency, where the blood vessels in the uterus that are supposed to transform into the blood vessels of the placenta do not change as they should.

This can lead to placental infarction, where the blood supply to the placenta is disrupted, resulting in the death of placental cells, placental abruption (where the placenta partially or completely separates from the uterus before childbirth) and structural abnormalities of the placenta that disrupt its normal functioning.

The net result of all these conditions is that the fetus does not receive sufficient nutrients and oxygen from its mother, thus affecting its growth.

- Fetal

Meanwhile, causes that arise from the fetus itself include genetic or chromosomal defects (eg Down syndrome) and congenital abnormalities (eg structural defects of the heart, kidneys, lungs or intestines).

Catching an infection while in the womb or being part of a multiple pregnancy (ie twins, triplets and so on) can also negatively affect a fetus’ growth.

SGA can also be categorised as symmetrical and asymmetrical.

In symmetrical SGA, all the baby’s measurements – length, weight and head circumference – are less than normal for their gestational age. In such cases, the cause is likely something that occurs or begins in early pregnancy, usually in the first trimester.

In asymmetrical SGA, the baby’s length and head circumference are normal, meaning that their brain and bone growth are as expected; however, their weight is low. This usually indicates an issue that occurs towards the end of the third trimester of pregnancy, as the fetus gains a lot of weight during this period.

Thus, pregnant women should ensure that they go for their antenatal check-ups in order to monitor for and manage any problems that might result in an SGA baby.

Complications of SGA

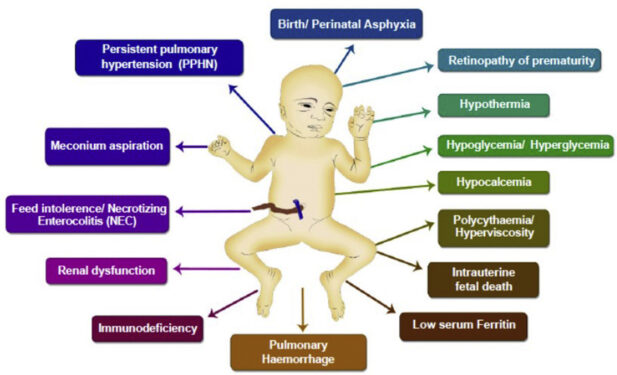

SGA babies may face certain problems after delivery due to their small size.

As they have only small amounts of fat or energy stored away, they may have a low body temperature at birth. This can result in hypothermia, where the body loses heat faster than it can produce it.

If this condition is prolonged, the baby can die as its heart and brain cannot function well at these sub-optimal temperatures.

The lack of fat and glycogen stored in an SGA baby’s liver can also cause hypoglycaemia, where they have low blood sugar levels that are unable to match their body’s needs. This can cause the baby to have seizures and/or brain damage.

If the hypoglycaemia is prolonged, the baby may die or develop long-term neurodevelopmental deficits, including cerebral palsy.

In addition, the problems that result in an SGA baby can cause them to undergo certain types of in-utero programming involving their metabolism and puberty.

As they are deprived of sufficient nutrients in the womb, such babies become “programmed” to hoard whatever nutrients and calories they receive. This means that after birth, they can very easily put on weight if their caloric intake is not carefully monitored.

Thus, SGA babies are prone to obesity and its associated conditions (eg diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, osteoarthritis and heart disease). And this “programming” lasts throughout their lifetime.

Their growth rate can also influence when they achieve puberty. SGA babies who catch up in their growth very quickly might experience early puberty. On the other hand, if they are slow in growing, their puberty might be delayed.

One more complication of SGA is persistent short stature. Generally speaking, SGA babies should be able to catch up in their growth within the first six months to two years of their life with good nutrition.

In fact, 85% of SGA babies achieve normal height and weight for their age and gender by two years of age. Some children require a longer time and there is still some leeway until the age of five to allow them to catch up in growth to their peers.

However, by five years of age, around 8-10% of SGA babies would still be abnormally smaller than normal, and this is the time that parents and doctors need to start discussing treatments for the child.

Managing SGA

Growth hormone therapy is the main treatment for SGA babies who do not manage to catch up in growth by the time they are four to five years old. This treatment will enable them to achieve their optimal final height as adults by improving muscle and bone growth.

In addition, growth hormone therapy helps increase the breakdown of lipids (fats), which will help tackle the tendency of SGA babies to accumulate fat and become obese.

Parents also need to help their children live healthy lifestyles in order to promote proper growth. Nutrition plays a critical role in the first two years of life in promoting a child’s growth.

However, it is essential for the diets of SGA babies to be carefully monitored as they are prone to becoming overweight.

On the other end of the scale, if SGA babies are not fed enough, they might become stunted. So, parents need to do a careful balancing act when it comes to feeding their SGA baby.

As they grow, parents also need to encourage and allow their children to be active, which will not only prevent excessive weight gain but also help stimulate the natural production of serotonin and growth hormone to help the child grow.

Such physical activity must be vigorous enough that the child’s heartbeat increases and they sweat.

Proper sleep is another essential component of growth. It is critical that children are asleep by 9pm at the latest as the peak time for the body to produce its natural growth hormones is between 10pm to 12am.

Sleeping later, as many Malaysian children tend to do, will cause them to miss this critical period of growth hormone secretion.

According to the National Health and Morbidity Survey (NHMS) 2016: Maternal and Child Health, 9.7% of babies born in Malaysia are SGA, with 6.4% being term SGA babies. However, paediatric endocrinologists are not receiving enough patients to match this statistic.

This means that many SGA babies are growing up shorter than they need to be as they are missing out on the treatment and management they could be receiving to help optimise their growth and improve their metabolic profile.

It is important that parents track their child’s growth carefully, especially in the first five years of life.

They can do this through regular measurements of their child’s height and checking these measurements against the appropriate gender- and age-based WHO growth charts, or through digital tools like the Growth Journey app* endorsed by the Malaysian Paediatric Association, which helps monitor a child’s growth through regular photos of the child and will alert parents if a worrying growth trend is detected. – Nov 3, 2022

Prof Dr Muhammad Yazid Jalaludin is a senior consultant paediatrician and paediatric endocrinologist at the Universiti Malaya (UM) Specialist Centre (UMSC). She is also the deputy dean (undergraduate) of UM’s Faculty of Medicine.

The views expressed are solely of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Focus Malaysia.

* The contents and features provided in the app are for information and educational purposes only. Please refer to your healthcare professional in case of any medical query or concern.

Main photo credit: Christian Wheatley