SINCE he took over the reins of the government in November 2022, Prime Minister (PM) Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim has been ruthless in his crusade to eradicate corruption.

He has set a target to improve the Corruption Perception Index (CPI) world ranking from 57th currently to 25th by 2033.

Whether all this is mere anti-corruption rhetoric as he joined his predecessors from the past five decades is for the readers to decide. One thing for sure, none of the past PMs have been bold enough to tackle the most obvious root cause and source of corruption.

Companies are the primary, if not the only creators of wealth. Consequently, companies are the source and breeding grounds for corruption and money-laundering to squander this wealth.

Companies can range from a one-person “Sdn Bhd” entity to the mammoth public listed companies.

They include government-owned, government-linked, statutory bodies or any government authority or agency that is incorporated under the Companies Act 2016.

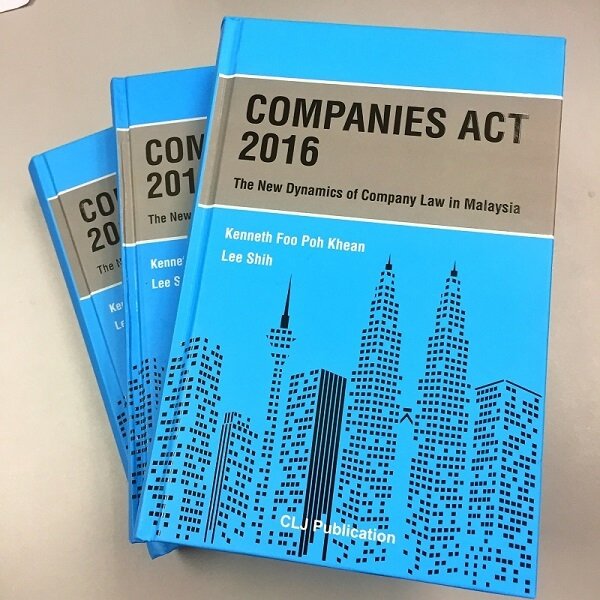

The Act is probably the longest piece of legislation which has over 600 primary sections in as many pages – not to mention the numerous rules and regulations. It makes legally binding rules from establishment and operations to winding up of a company.

Loopholes abound

Any violation of the Act especially corruption, money-laundering and abuse of power can be easily detected and curtailed through annual, periodic and material changes reporting to the authorities concerned.

Therefore, the primary focus of any anti-corruption measure should be through the Companies Act 2016 and related legislation such as the Securities Commission Act 1993 and Capital Market and Services Act 2007.

The Companies Act 2016 states that the business and affairs of a company” shall be managed by and be under the direction of the Board (of directors)” (Section 211). Section 212 states that a director shall exercise reasonable care, skill and diligence through having the necessary skill, knowledge and experience.

Section 213 states that directors should exercise business judgement for a proper purpose and in good faith, have no material personal interest and in the best interest of the company.

Therefore, the shareholders or owners of the company have no legal right to interfere with the business and affairs of the company.

To protect their interests, shareholders can only appoint the directors, set the limit of powers of the board of directors in managing the company, and appoint the external auditors, among others.

The Companies Act 2016 does not recognise such organs as Board of Advisors, Advisor Emeritus, the office of the PM, Finance Minister or any minister in the business and affairs of a company.

The underlying principle is that a company and its shareholders are distinct separate entities. A shareholder gets to limit his personal liability to only his shareholding and should therefore not interfere in the business and affairs of the company or worse still, steering it to his personal benefit. This principle has been affirmed by several Federal Court rulings.

Integrity compromised

Likewise, the board or any of its directors who claim to be influenced by the shareholders, however powerful they may be, is guilty of a criminal offence and should be charged in the first instance for mismanagement of the company.

The only recourse for a director is to tender his resignation there and then if he cannot stand up against the shareholder.

It is common practice in GLCs for the government as shareholder to appoint politicians or senior serving or retired civil servants as directors.

Would such politicians or civil servants have the qualifications, skills or experience to run a competitive market driven business (Section 212) or can exercise business judgement (Section 213) in the best interest of the company without influence from the shareholder.

Serving senior civil servants are often appointed to the Board as directors purportedly to protect the interests of the government. I believe many of them are paid director’s fees and allowances on top of their salary as career civil servants.

If such fees and allowances are retained by the civil servants, wouldn’t that compromise their role as full-time civil servant, director and representative of the government as shareholder?

Anwar who is also the Finance Minister has reportedly refused and returned the fees and allowances paid by Khazanah Nasional Bhd. That is a bold and necessary move. Would he practice that across-the-board, so that the interest of the companies they manage would not be compromised?

Anatomy of corruption as cancer

Anwar has likened corruption to cancer. Based on previous failed and struggling government companies, we can construct an anatomy of corruption spreading like cancer against the backdrop of the Companies Act 2016.

The five stages of corruption and money-laundering can be represented thus:

- Stage 0

There are early signs of corruption but has not become invasive. Usually, symptoms can be easily dealt with at this stage by applying the provisions of the Companies Act 2016.

- Stage 1

A pattern of symptoms appears. The company may be slacking in its operations, missed revenue targets, escalating expenses or facing staff discontent but nothing serious. Any symptoms can be treated and contained internally by applying the Companies Ac 2016.

- Stage 2

The symptoms start to manifest. Poor product or service quality. Cash flow problems. Staff demoralised and delayed salary payment. At this point, the effect of a mix of qualified and unqualified directors managing the business and affairs of the company becomes apparent.

Revenue and profit dives. Complaints on violations of the Companies Act 2016 surfaces. Auditors will sign off on financial statements with caution on several matters but not warranting a qualified report. The company may venture into taking over other successful business to cover up and sustain its operations.

- Stage 3

All these symptoms become severe and cripple the company. The company makes deep losses and needs injection of taxpayers’ money to survive.

There will be frequent changes of board members. The company will invest heavily on expensive consultancies for business-restructuring and turn-around plans while the government will be forced to pump in more money.

Staff may leave and whistle-blowers emerge but will be swiftly silenced. The Companies Act 2016 demands absolute transparency but matters will be put under official secret. Multinational auditors will leave and new local auditors will be appointed.

The required reporting to the Companies Commission Malaysia (CCM) will be deliberately delayed or halted. The National Audit Department may uncover financial irregularities, mismanagement and abuse of power. Enforcement agencies such as the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission (MACC) and the police may commence investigations.

- Stage 4

The company is either dead or dying buried by mounting debts. The government may rescue the company by bringing it under its fold. All losses will be written off.

Depending on political divide, culprits may be brought to book. The directors of the company will move on to mismanage other companies with impunity.

Anwar has vowed to bring radical and bold reforms even at great personal and political risk. Will he be radical and courageous enough to bring these reforms and nip corruption before it becomes invasive at the company level by strengthening the institutions responsible for implementing the Companies Act 2016 and other related Acts? – Oct 4, 2024

Raman Letchumanan is a former senior official (environment) in Malaysia and ASEAN, and a Senior Fellow at Nanyang Technological University Singapore. He is an accredited accountant (Malaysia/UK) and has a PhD in environmental economics, among other qualifications.

The views expressed are solely of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Focus Malaysia.