MALAYSIA and China marked the establishment of formal diplomatic ties on May 31, 1974 during the height of the Cold War. The then prime minister Tun Abdul Razak signed the joint communiqué with premier Zhou Enlai, making Malaysia the first ASEAN country to establish ties with China.

In 1974, Malaysia boasted a robust and self-reliant economy with its gross domestic product (GDP) standing at US$9.5 bil, while China’s was US$144.2 bil and the US’ was US$1.54 tril. Fast forward to 2022, Malaysia’s GDP stood at US$406.31 bil versus China’s US$17.9 tril and the US’ is US$25.46 tril which provides the context to the evolving trade relations.

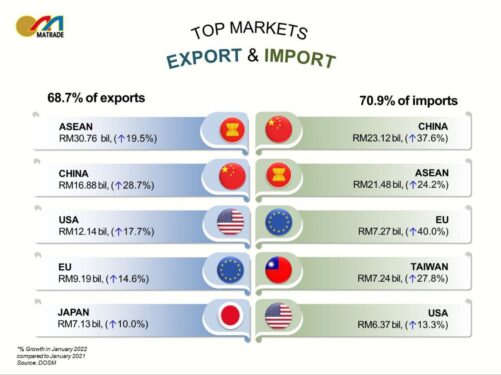

In 1990, the total trade between Malaysia and China recorded US$1.18 bil, climbing to US$7.6 bil in 2001 and US$14.3 bil in 2002. By 2021, China had maintained its position as Malaysia’s largest trading partner for 14 consecutive years, accounting for 17.1% of Malaysia’s total trade at US$104.4 bil.

While the economic ties have proven beneficial, Malaysia faces challenges in expressing candid views on sensitive matters due to its economic dependence on China. The lopsided trade relation raises concerns about Beijing’s leverage over Malaysia’s foreign policy, economy and domestic politics.

Malaysia finds itself increasingly muzzled in its ability to speak frankly and openly about matters that should be routine, especially over the South China Sea and the treatment of Uyghurs and other groups.

Or even the perceived pressure in matters like the 5G roll out which is being opened to accommodate China-based companies despite Malaysia’s initial decision to implement a Single Wholesale Network (SWN) model.

Lopsided deal

There are concerns over the proliferation of apps such as TikTok which have drawn the attention of security officials in many countries, hence being partially or totally banned in more than a dozen countries.

This is especially of note in Malaysia with the app playing a key role in garnering votes for certain political parties, influencing political opinions in Malaysia and raising questions about foreign influence.

While Malaysia may have started its bilateral relations on equal terms, it has certainly been dwarfed with China’s growth.

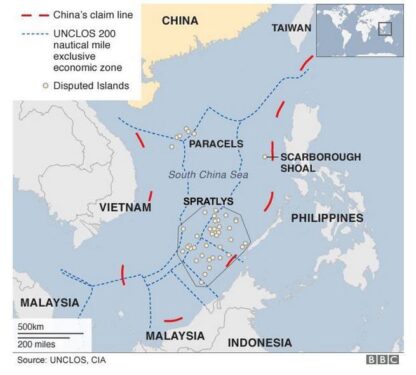

This would not be a problem as Malaysia certainly has dealt with more powerful countries in the past – especially Western ones – but China is intent on carving off sections of Malaysia’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in the South China Sea through its “nine-dash line” which was re-affirmed in August. China certainly does not hide its intentions.

While in the past bilateral trade had been of benefit, Malaysia’s participation in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has opened itself to yet more vulnerabilities.

The flagship BRI project in Malaysia is the East Coast Rail Link (ECRL), a mega railway that is meant as a land bridge connecting Port Klang and Kuantan Port but the viability of the project – not to mention the enormous debt Malaysia has taken on for its construction have raised many concerns.

Will this project ever add to Malaysia’s economy? Already the project has fallen far short of the promised job creation. Barely 4,000 Malaysians were employed when it was initially touted as being able to provide tens of thousands of jobs. Additionally, the project has resulted in swathes of forest, including protected areas, being cut away.

And once the ECRL is launched, there are doubts over whether its passenger and cargo services will be able to pay off the cost. Of course, no one is considering what disruptions are in store for bus and freight lorry companies which will see their market share reduced.

For those seeking answers on ECRL, a quick look at Cambodia, Laos, Sri Lanka or any number of African nations may be enough.

Vassal status

We have to also consider how our relations with China are holding back our development and upskilling of the Malaysian workforce. Malaysia being a major bauxite exporter relies on quick and easy extraction for quick profits.

Look at Indonesia which is building aluminium smelters instead of simply exporting bauxite. Why would Malaysia ever move up the value chain if it can rely on exports of raw materials with a resource-hungry China on its doorstep? And this is just one industry.

Malaysia must move on all fronts if it is to reaffirm its independence, whether on industrial, economic, security and foreign policy issues. The current trajectory indicates a dash towards a vassal status.

But it is not too late to turn things around. Even as the geopolitical situation between the West and China heats up, Malaysia must seize this opportunity to put its foot down and make its mark. It must pursue a truly non-aligned policy while leveraging on its traditional trade and security partners to keep a voracious China at bay.

It does not take a massive military or other grand measures to secure one’s national interest. Walking the talk and sticking to the principles of a rules-based order, one that has kept the peace for decades while building up its self-sufficiency and a credible deterrent along its maritime EEZ are small but vital steps.

In trying to walk the middle path, Malaysia must avoid a dangerous tilt. – Dec 21, 2023

Economist Samirul Ariff Othman is an international relations analyst and a senior consultant with Global Asia Consulting (GAC).

The views expressed are solely of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Focus Malaysia.