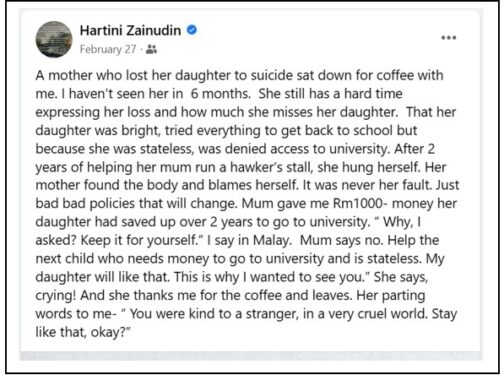

DATUK Dr Hartini Zainudin who is the vice-president at Voice for Children jotted on her Facebook (FB) on Feb 27 this year about a girl who committed suicide when she had just passed the age of 21.

The activist who co-founded Yayasan Chow Kit said the girl had worked for two years helping her mother run her chicken rice stall in Petaling Jaya. She had saved up some money, hoping that she could attend college like many of her friends.

She was brilliant. However, one thing that set her apart from her other friends of the same age was her statelessness.

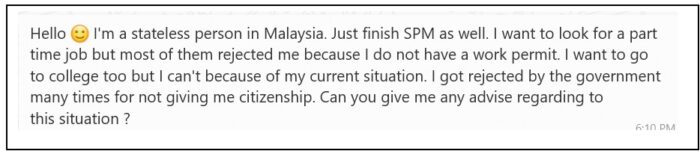

In 2018, she had connected Dr Hartini on FB messenger for the first time, introducing herself as a “stateless person in Malaysia.” She had just completed her SPM then and wanted to get some advice from Dr Hartini about her situation.

“I want to look for a part-time job but most of (the employers) rejected me because I do not have a work permit,” she said. “I want to go to college too but I can’t because of my current situation.”

That her application for citizenship was rejected many times by the government had dashed all her hopes for a good future.

Looking back, a teary-eyed Dr Hartini told FocusM: “I was devastated and felt absolutely helpless. This message was sent to me in 2018. About two years later, she hanged herself. Even six months later after she committed suicide, her mother was still finding it hard to accept what had happened.

The story of this girl can be told many times with all the younger ones who were born in Malaysia, yet without a citizenship.

The Star, for example, highlighted the case of a girl, Belle Chok who is stateless and suffering from systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). She had to painstakingly raise funds for her medical treatment after she passed the age of 12.

Coming under Segambut MP Hannah Yeoh’s constituency, Yeoh had tried to assist but to no avail in the past. In Bandar Menjalara and Bukit Maluri alone, there are at least six other cases.

With some funding and support from Yeoh, the community provided some form of support to five of the stateless children from just one family.

Innocent children born out of wedlock are automatically stateless. If one of the child’s parents is a foreigner, this gets more complicated. Despite being born and raised in Malaysia, they do not enjoy the same privileges as their friends.

They cannot open a bank account or hold a passport. They are stateless, and simply feeling hopeless in a country they have always called their home.

To ask them to apply for their citizenship in the country where one of their parents belong to is just too “ridiculous” to say the least. Most of these children have never even travelled overseas, given that their application for a passport would never be approved.

This dilemma faced by thousands of other children is the result of a minor amendment to the federal constitution on Jan 31, 1962 when lawmakers voted to change Malaysian citizenship from jus soli (a principle of law of nationality based on place of birth) to Jus sanguinis (citizenship is determined or acquired by the nationality or ethnicity of one or both parents).

Once amended, there may be a floodgate of many thousands of children becoming officially Malaysian citizens. This may create some strain to the healthcare and education system but it will also contribute to the supply of human resources in the country. – May 31, 2023.